When mosquitoes bite, the effect may be much more than just skin deep. Researchers at the Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Texas, found mosquito bites can meddle with our immune systems for days, right down to our bone marrow. Mosquito saliva helps dengue replicate and spread around our bodies. Their findings might mean we need to rethink how we prevent, diagnose and treat dengue and other mosquito-borne diseases.

“We realized we knew little about what happens inside us after a mosquito with dengue bites,” Professor Rebecca Rico-Hesse, a virologist at Baylor College of Medicine, told us. “So, we developed a model to show how dengue fever behaves inside a human, using ‘humanized’ mice.”

Only humans can catch dengue; mice and other animals can’t. So, to study what happens after a bite from a mosquito infected with dengue, the team implanted specific human stem cells (the ones that make our immune system) into a group of mice. These mice were now primed and ready to catch the virus.

But only some of them caught dengue when the researcher injected the virus into them. “We decided to take a more natural approach to dengue transmission and let infected mosquitoes bite the mice,” said Professor Rico-Hesse. “That changed everything.”

Mosquitoes courtesy of Baylor College of Medicine

When bitten by mosquitoes, the mice had a higher infection rate, worse rash, and lower platelet levels. They had pretty much more of all the things that are the normal signs of dengue fever, and the virus remained in their blood for longer.

Examining the bite

Seeing mosquito bites were far better at passing on dengue than a syringe, the team realized they had never actually studied how a mosquito bite alone affects us. What they found was totally unexpected: mosquito bites actually change our immune system.

“We saw changes in immune system cells seven days after a mosquito bite, sometimes right down to the cells in the bone marrow,” said Professor Rico-Hesse. “If mosquitoes are constantly biting us, they are constantly affecting our immune system.”

So how does this happen?

When a mosquito bites, it injects saliva first to make it easier to draw blood. That saliva “probably contains more than 100 active proteins,” according to Professor Rico-Hesse. “These proteins don’t just affect us locally area around the bite; they also attract and affect our immune system cells.”

Are mosquito bites giving the dengue virus a ride?

Add the dengue virus, and you can see how the mosquito saliva is giving dengue a helping hand. The proteins in the saliva attract our immune system cells, which then take the dengue virus down into our bone marrow.

But the immune system cells in our bone marrow aren’t so good at fighting antigens (foreign bodies such as infections or viruses). The virus can spread virtually unchallenged into the new immune system cells our bone marrow is tasked with forming. Our bone marrow is effectively “serving as a sanctuary for the virus to replicate.”

Even more concerning is that you can’t necessarily detect dengue in a blood sample when the virus is busy replicating deep down in our bone marrow.

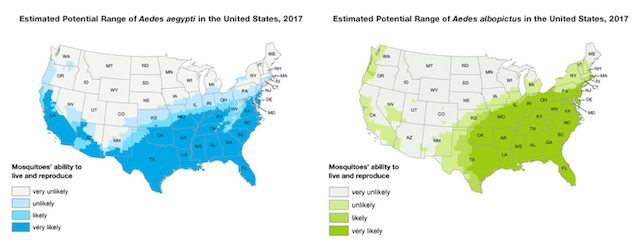

Learn how the CDC is fighting the spread of dengue in the USA

And that’s not all. After the bone marrow has finished forming new immune system cells, these are sent out to different tissues to do their work. Some make their way back out to our skin seven days after the initial mosquito bite. Another mosquito could then come and bite us and become infected with the dengue virus – without us even knowing we have dengue.

We have a problem

In a nutshell, this means a person showing no signs of dengue in a blood sample could still be contagious to a mosquito. “If we have people walking around with dengue in their bone marrow when they don’t even realize they’re infectious, then we have a problem,” says Professor Rico-Hesse.

“If it turns out that the very core of our immune systems is getting infected with dengue, then we need other types of cells to detect the infected immune system cells,” she continues. “And we need a therapeutic that can get rid of the virus inside immune system cells, right down to the bone marrow.”

Professor Rico-Hesse and her team are next planning to investigate what happens inside us at a cellular level if the mosquito is a vector for not only dengue but also Zika and chikungunya. She explains: “We have to repeat our research with these three viruses and look for similarities and differences in how mosquito saliva affects dengue transmission and distribution to the tissues in the human host.”

The team’s findings could completely transform our understanding of dengue, dengue transmission and what we need to do to prevent this terrible disease.

—

Help create an international day focused on raising awareness of dengue fever and the prevention of this disease. Sign and share our petition for a World Dengue Day.