- by Alison

How Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes are reducing dengue outbreaks

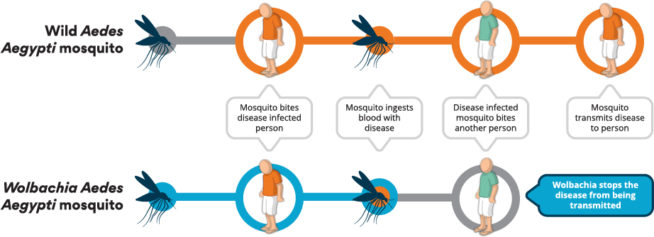

A naturally-occurring bacteria, Wolbachia can be found in around 60% of insect species, including some types of mosquito. Wolbachia, however, it is not usually found in the Aedes aegypti mosquito. But artificially infecting an Aedes population with Wolbachia reduces the mosquitoes’ ability to transmit dengue (and other diseases) to humans. In this, the first in our two-part series on Wolbachia, we look at how Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes hold the key to reducing dengue outbreaks.

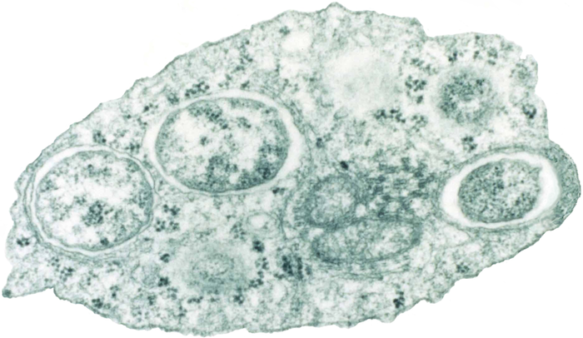

Whenever Wolbachia bacteria infects an Aedes population, the bacteria significantly reduces the risk of a dengue outbreak. The Wolbachia bacteria, as you can read here, compete for the resources that the dengue virus needs to thrive (amongst other things), stopping the virus forming infections inside the mosquito.

How the World Mosquito Program’s Wolbachia method works. Image via the World Mosquito Program

So, how can we help Wolbachia bacteria invade an Aedes population? By releasing Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes into a wild Aedes population over a period of a few weeks. The mosquitoes then breed with the wild mosquito population, passing the bacteria from generation to generation and replacing the wild mosquito population over time. When the invaders mate with the local population:

- The female Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes transmit the Wolbachia to all of their offspring, which are mostly female.

- The male Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes’ partners produce eggs that don’t hatch – a phenomenon known as cytoplasmic incompatibility.

Not all Wolbachia are the same

The Wolbachia’s ability to invade an Aedes population depends on several factors, including the specific strain of Wolbachia and the temperature of the environment where the Aedes larvae are reared.

Researchers have shown cytoplasmic incompatibility is less likely to occur in infected larvae reared between 26°C and 37°C with certain Wolbachia strains. Some eggs still hatch and grow into mosquitoes that can transmit dengue. The researchers also found that, at similar temperatures, females infected with some specific strains of Wolbachia did not pass the bacteria to their offspring.

The researchers concluded: “These findings have implications for the potential success of Wolbachia interventions across different environments and highlight the importance of temperature control in rearing.”

Scientists running dengue elimination programs need to choose Wolbachia strains carefully. In Malaysia, The Star reports that Australia, Brazil, Indonesia, Colombia, and Vietnam have released Aedes infected with the wMel strain of Wolbachia, but China is using the wMel-Pop strain. It also notes: “The wMel-Pop strain is a good dengue blocker, but it was found to cause high mortality among adult Aedes mosquitoes”.

A high mortality rate means the Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes may struggle to increase their numbers amongst the wild Aedes population, preventing them from suppressing the dengue-transmitting mosquitoes.

Numbers are important too

It’s not just the strain of Wolbachia that’s important, the number of Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes released is also critical to success.

A recent study found between that 20% and 30% of the Aedes population needs to be infected with Wolbachia for the bacteria to take hold among the population. Below that threshold, the Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes will gradually reduce in number and be lost in time. Researchers note: “As a patch of Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes gets smaller, the proportion of individuals within that patch that are immigrants from surrounding Wolbachia-free populations gets larger.”

There are believed to be two reasons why the larger proportion of immigrants leads to a continued decline in Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes. Firstly, when the levels of Wolbachia are low in an Aedes population, wild females rarely mate with the Wolbachia-infected males, and so they continue to produce Wolbachia-free offspring.

Also, female mosquitoes with Wolbachia are not quite as fertile as their bacteria-free counterparts; they don’t produce as many offspring. When Wolbachia levels are low, the Wolbachia-free females continue to outbreed the females mosquitoes with Wolbachia until the Wolbachia eventually disappears.

The World Mosquito Program also failed to establish Wolbachia-infected Aedes mosquitoes when it tried to replace the wild population in a small area because Wolbachia-free mosquitoes from surrounding locations migrated into the area. It also found that roads, rivers, and forests could get in the way, hindering mosquito movement.

Any downsides to using Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes?

One of the main concerns around Wolbachia programs is that they could make communities complacent. A study into the risks associated with the release of Wolbachia-infected Aedes mosquitoes into the environment to control dengue found there was a small risk that households would decrease their mosquito control efforts if they felt dengue transmission was less likely. It felt projects could address this concern by increasing community education.

Other studies have raised concerns that Wolbachia could increase some vector-borne pathogens in insect populations. Research published in 2014 found that Wolbachia enhances West Nile Virus (WNV) Infection in the Culex tarsalis mosquito. The main message coming from the study was that we need to keep an eye out to ensure Wolbachia doesn’t increase a mosquito population’s ability to transmit one virus as we employ it to lessen the population’s ability to transmit another. It also notes that Wolbachia can transfer from one insect species to another, so we also need to ensure we don’t end up with any unforeseen consequences as a result of that happening.

Look out for the second half of our series on Wolbachia when we compare the differences and similarities between Asia’s Wolbachia programs.

—

Now it only takes seconds to reduce the impact of dengue. Click below to report dengue fever activity in your area to Dengue Track, and create a record that helps experts better understand this disease.