- by Gary Finnegan

Dengue in Colombia: is it ready for the vaccine?

Dengue in Colombia is not a new phenomenon. In fact, more than half of Colombia’s 25 million population is at risk of dengue fever. A new research project aims to explore whether the Latin American nation is ready to embrace the dengue vaccine.

Dengue is endemic in Colombia. Most Colombians live in areas where mosquito-borne illnesses are a daily threat. The country’s largest recorded outbreak came in 2010 when more than 157,000 cases were reported, and it has been hit hard in recent years by Zika outbreaks.

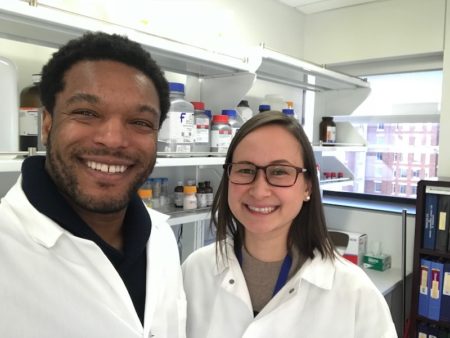

As an expert in arboviruses that cause Zika, chikungunya and dengue fever, Dr. Aileen Chang, frequently travels to Colombia. Dr. Chang is an Assistant Professor of Medicine at George Washington University Medical School in Washington DC and works with NGOs and government officials on health projects.

Dr. Aileen Chang fighting dengue in Colombia pictured here with Break Dengue’s Aaron Hoyles

‘I’ve treated patients affected by arboviruses for several years and studied Zika and chikungunya in Colombia to understand how to prevent and treat these infections,’ she told Break Dengue.

Now, inspired by the Break Dengue Community Action Prize, Dr. Chang has dengue in her sights. ‘A collaborator in Colombia in Colombia encouraged me to apply for the prize so that we could launch an initiative targeting dengue prevention.’

Having discussed dengue vaccination with colleagues on the ground in Colombia, Dr. Chang found the vaccine was in very limited use. In fact, awareness of its existence was very low. ‘We wanted to do a more scientific study of the feasibility and acceptability of introducing dengue vaccines to Colombia.’

Dr. Chang’s team won $10,000 through the Break Dengue prize and will begin developing a detailed questionnaire in the coming months. The plan is to survey patients, health professionals and to engage with public health administrators to understand whether Colombia has the appetite and resources to introduce a vaccine program in endemic areas, like the dengue immunization program launched by Parana State in Brazil last year. It will include questions on disease awareness, demand for vaccination and acceptability of the vaccine.

‘We want the survey to be robust and culturally resonant so we are drawing on the WHO vaccine preparedness document, and we will test the questions to ensure the translation is suitable for the audience,’ explains Dr. Chang. ‘After that, we will introduce it in three areas of Colombia with the highest levels of mosquito-borne illnesses.’

Dr. Chang’s links to the Universidad El Bosque, Fundacion Santa Fe, and Colombian government will provide access to officials who can help answer key questions about the feasibility of vaccine introduction. ‘We have particularly strong contacts in the Atlantico Department along the northern coast and have a large team of people based in Colombia,’ she explains.

Fighting dengue in Colombia integrating vaccination

The challenges for a low-resource country, albeit a fast-growing one, is to find the resources required to procure a vaccine, develop infrastructure for vaccine delivery and disease monitoring, as well as cold-chain, logistics and training health professionals.

Colombia’s health service is funded through a mix of public and private health insurers. Employees in the public service are entitled to publicly-funded care while others can – if they have the money – purchase private health insurance policies giving them access to multipurpose clinics.

This makes rolling out vaccination a complex prospect in Colombia, a country experiencing steady economic growth but with significant income inequality challenges.

‘There is a real divide between rich and poor,’ explains Dr. Chang. ‘The poorer areas are worst-hit by outbreaks of arboviral diseases, due to unplanned urbanization and water supply issues which provide mosquito breeding sites.’

She says that the gap between the haves and have-nots is widening because diseases like dengue and chikungunya are disproportionately affecting low-income households without access to healthcare. ‘People who have previously had one arboviral disease are at a higher risk of subsequent mosquito-borne infections. And if you develop an illness you may be unable to work for a significant period, reducing your earning capacity.’

However, Dr. Chang says that her Colombian partners are keen to embrace new technologies and to build research capacity in their country. ‘There is a big push in Colombia to do more research,’ she says. ‘Academic institutions are particularly keen to work with partners in the US and local health ministers have reached out to our group asking for support in developing evidence-based responses to the challenges they face.’

Dr. Chang’s project on dengue vaccination could be a step in the right direction. Any measures that effectively curb the impact of arboviruses in developing countries can help break the cycle of poverty and ill-health.

—

Click below to boost dengue surveillance near you and report your local dengue activity to Dengue Track.

https://www.breakdengue.org/dengue-track/about/