- by Alison

Dengue in Africa: Why we urgently need to wake up to the public health threat on the continent

Dengue is no stranger to West Africa. The potentially deadly virus might even be endemic in many countries in the region. The problem is, nobody knows the real status of dengue in Africa. And with the numbers not understood, dengue does not feature highly among governments’ health priorities. We spoke with Justin Stoler from the University of Miami’s Departments of Geography and Regional Studies and of Public Health Sciences to find out more. He has spent many years investigating dengue fever, particularly in West Africa.

Despite the almost certain presence of dengue in Africa, the true burden of the disease is unknown, as highlighted by the World Health Organization in its Global Strategy for Dengue Prevention and Control 2012-2020:

“For Africa, there are insufficient data from endemic countries to make even rough estimates of burden.”

The strategy goes on to note that an article, “Dengue virus infection in Africa” published in Emerging Infectious Diseases in 2011 reported:

“During 1960-2010, a total of 22 countries in Africa reported sporadic cases or outbreaks of dengue; 12 other countries in Africa reported dengue only in travelers.”

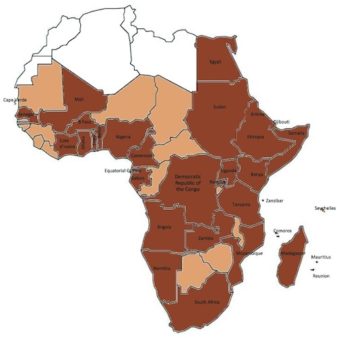

The article maps the presence of both dengue in Africa and Aedes aegypti across the continent, with brown indicating the 34 countries where dengue is present, light brown indicating the 13 countries with Aedes aegypti but no dengue, and white indicating countries with no data available.

Of the countries that make up West Africa (Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, Ivory Coast, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Liberia, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Togo and Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha), around half reported the presence of dengue, with the remaining reporting the presence of Aedes aegypti.

Just last year, we reported on a major dengue outbreak in Burkina Faso and the World Health Organization’s Disease Outbreak News reported a dengue outbreak in the Ivory Coast.

“The landscapes of West Africa certainly support Aedes aegypti,” says Stoler. “The mosquito has been present for most of the 20th Century; it would seem almost impossible for dengue not to be circulating at some level – but nobody had really studied it.”

Fevers misdiagnosed as malaria

Worse still, whenever someone in sub-Saharan Africa [which includes West Africa] has the high fever that could indicate dengue, they’re all too often diagnosed with malaria. Why? Because the two diseases present similarly, and limited health care resources do not stretch to confirming the actual illnesses in the lab.

Stoler explained how malaria, which affects more than 200 million Africans each year, has been “institutionalized as the disease that you have when you have fever and headaches.

People are presumptively diagnosed with malaria and given antimalarials all the time, even when the parasite is not circulating.”

This misdiagnosis is still commonplace despite, the burden of malaria falling 20% in the region between 2010 and 2016, according to the WHO Malaria Report. “Research over the last five years has shown that only 10 to 20% of febrile children actually have malaria, yet many more are presumptively diagnosed with it,” says Stoler. “Other infections, including dengue, are being missed.”

Previous dengue exposure uncovered

Given that Aedes was known to be circulating in West Africa, Stoler wanted to find out what viral diseases the mosquitoes were actually transmitting – including dengue.

In his early research into dengue in West Africa (conducted in collaboration with Gordon Awandare, Director of the West African Center for the Cell Biology of Infectious Pathogens [WACCBIP] at the University of Ghana), Stoler found that in many parts of sub-Saharan Africa “up to a third of patients suffering from acute fever do not receive a correct diagnosis of their infection.” He concluded that “the true burden of diseases such as typhoid, influenza and dengue fever are likely understated.”

Read about the impact of climate change on dengue

These conclusions came from analyzing samples from 218 feverish children in Ghana, all of whom had laboratory-confirmed malaria. The samples revealed previous exposure to dengue in 21.6% of samples and recent exposure in 3.2% – but no current infections.

Suspected malaria found to be dengue

But the laboratory had also confirmed that some patients with a high fever did not have malaria. The researchers became convinced that there was a real possibility these patients might have dengue.

Stoler and Awandare continued their research, this time analyzing blood samples from 166 Ghanaian children attending hospital with acute fever and suspected malaria. Their analysis found two children suspected of having malaria had, in reality, a strain of the dengue virus closely related to the DENV-2 serotype isolated in a 2016 outbreak in nearby Burkina Faso.

The study was the first to isolate the dengue virus in feverish children with suspected malaria, concluding: “This DENV-2 strain may soon become regionally endemic [in West Africa] if it has not already.”

Stoler expanded on this during our interview, saying: “This virus strain has most likely been migrating throughout West Africa, following local population movements. But we don’t quite know the extent to which this – or any – strain of dengue is already endemic because dengue isn’t generally considered in Africa when people have an acute fever.”

Dengue in Africa: attention needed

The receding burden of malaria is one of four global health trends that Stoler firmly believes indicate we must give urgent attention to the spread of dengue in Africa, the others being climate change, emerging pesticide resistance and the delayed promise of a dengue vaccine.

“The decline in malaria transmission in many endemic areas of Africa over recent years means there is an urgent need for physicians to diagnose acute fevers accurately,” says Stoler.

The search is on for diagnostic solutions that allow physicians to test for multiple pathogens at the same time. “That’s the type of thing we are experimenting with,” says Stoler. “We are piloting a customized card that can test for dozens of different infections, all with one blood sample.”

While new diagnostics will be important for identifying infections beyond malaria, with dengue being one of the primary suspects, there is also an urgent need for re-education – not only of the public but also of the “entire medical establishment,” as Stoler puts it. “There are other possibilities they need to be considering in their diagnosis.”

The immediate challenges are two-fold: convincing the medical establishment that misdiagnosis is, in fact, a problem, and persuading national governments that dengue demands their attention.

“We have held dissemination meetings with the top hierarchy of the Ghana Health Service, and I believe they are taking the threat very seriously. So, we expect to see an increased and more coordinated surveillance program soon,” says Awandare.

If you have experience with dengue in Africa, we’d love to hear your story. Or maybe you were diagnosed with malaria but suspected your fever was actually dengue or another infectious disease.

—

Help experts better understand this disease. Click below to create a record of dengue activity in your area.