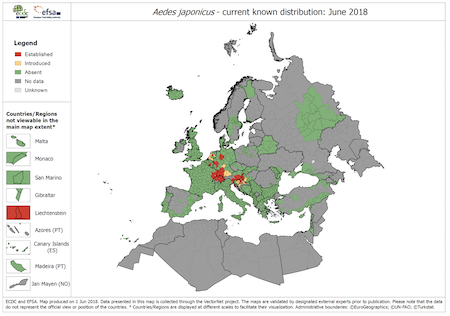

Aedes mosquitoes continue to expand their reach around the globe. Halting the spread of this nuisance is one piece of the jigsaw in the complex fight against dengue. Preventing these vectors from transmitting the virus is another. And that is exactly what the World Mosquito Program (WMP) aims to do.

We last spoke with the WMP around two years ago when we discussed how Wolbachia bacteria are reducing the impact of dengue. At that time, we examined how the WMP is using Wolbachia-infected Aedes mosquitoes to reduce the virus’ ability to replicate and mosquitoes’ ability to transmit the disease.

Expanding WMP operations

We recently spoke with Program Director Professor Scott O’Neill. He told us how, as a not-for-profit, the initiative’s goal is to “continue expanding to more countries as countries wish to learn about our technology.”

The initiative has made some significant progress in that direction over recent years. It has:

- established an Oceania hub based at Monash University in Melbourne, Australia, and is now setting up its Asia regional hub in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam to help support countries locally as it expands its operations globally.

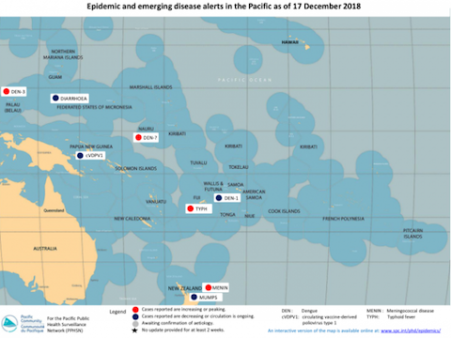

- commenced releases of mosquitoes with Wolbachia in Kiribati, Fiji and Vanuatu and welcomed New Caledonia as the fourth country in the Pacific to commence a project.

- announced that Mexico has become the first country in Central America to join the program, with La Paz set to be the first city to release Wolbachia mosquitoes.

The WMP is now releasing Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes in eight countries, with releases in India and Sri Lanka also in the pipeline. A total of 12 countries are embracing its approach, including, in addition to those countries already mentioned, also Australia, Colombia, Indonesia and Vietnam. “We’re hoping that within the next year or so we’ll be operating in 17 countries,” adds program director Professor Scott O’Neill.

Innovating for scale

As it deploys more projects in different locations around the globe, the WMP is continually learning and adapting its approach to improve how it releases its Wolbachia mosquitoes. Its goal is to become more efficient and more effective and to make its approach as affordable as possible. Optimising operations is not only key to expanding operations but also to reducing the cost of deployments – the WMP is targeting around US $1 per person protected.

The WMP recognised that it needed to understand how best to deploy the technology at scale. “Having done many successful small to intermediate-sized projects, we must learn how to deploy to cities of many millions of people,” says Professor O’Neill. “The challenges associated with operating at that size include mass production of mosquitos, deploying them most efficiently and scaling up community engagement.”

Starting with community engagement, the WMP has already adapted its approach to be more efficient at a larger scale. Professor O’Neill described how “community engagement is less intense than it used to be,” adding that the WMP was incorporating “more of our communications campaigns and less of the very intensive face-to-face community engagement” into its projects. He also confirmed that partners are helping to facilitate community engagement and that the technology is now seeing broad acceptance globally.

Efficient release operations

The community is also taking a greater role in actual mosquito releases. At the same time, the WMP is looking at alternative ways of releasing both mosquito eggs and mosquito adults efficiently at scale.

Its first unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) trial got underway in Fiji last November in collaboration with not-for-profit WeRobotics and local experts, . “Although this work is in its very early stages, there is potential for UAV technology to help distribute mosquitoes with Wolbachia across large cities,” says the WMP’s Project Coordinator in Fiji, Mr Aminiasi Tavui, in a WMP news article.

As well as adapting how it releases its mosquitoes, the WMP is also refining where it releases them. “We used to release mosquitos everywhere in a target area,” said Professor O’Neill. “Now, through experience, we’ve realised that we only need to release them in a subset of areas to be effective; that also means we don’t need to release, and therefore produce, as many.”

Effective dengue blockers

Ensuring the Wolbachia-infected Aedes aegypti mosquitoes are effective at blocking the dengue virus – and therefore less likely to transmit it to the humans they bite – is critical.

A large-scale efficacy trial in Yogyakarta in Indonesia still has around a year left to run. While the study aims to rigorously evaluate the impact of Wolbachia bacteria on the transmission of dengue and other mosquito-borne diseases, the Professor confirms that in all locations the initiative is finding that “once we deploy Wolbachia at high levels, we see local dengue transmission collapse.”

We asked Professor O’Neill about his recent research into the susceptibility of Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes to dengue. The study found Aedes mosquitoes reared in the field were less susceptible to dengue infections than those it was rearing in its labs. He confirmed that “field mosquitoes are stronger dengue blockers than mosquitoes grown in the lab”.

He explained that this meant second-generation mosquitoes, the offspring of the laboratory-reared mosquitoes the WMP is releasing, are even better at halting dengue in its tracks. “It’s a really nice result to get,” he added. “It means our measurements from the laboratory of the potential impact of our technology are probably conservative.”

As the WMP continues to expand to more countries around the world, it is also exploring how it can also help in the fight against Zika, chikungunya, yellow fever and other viruses transmitted by Aedes aegypti.

We can’t wait to see how the WMP approach evolves in the coming months and years. We’d love to hear about your own novel approaches to halting dengue transmission. Contact us with your stories.