Estimating the economic cost of dengue has never been easy. After all, in addition to the cost borne by public healthcare systems, there’s also families’ economic loss to consider. And for patients who don’t attend health facilities, the disease and its cost often remain hidden. A recent study used data gained from dengue vaccine trials to look at the cost of dengue in the children participating in that trial, comparing findings between those who had been vaccinated against the disease and those who hadn’t.

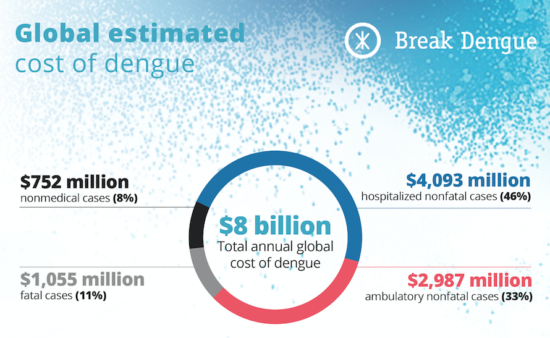

Over the years we’ve regularly looked into the burden of dengue. Our 2016 infographic on the cost of dengue, estimated the average cost of an individual dengue case to be US$151, with a total annual global cost of US$8.89 billion.

Back further, in 2009, World Health Organisation Guidelines for dengue diagnosis, treatment, prevention, and control quoted research into the economic cost of dengue conducted in eight countries in the Americas and Asia in 2005 and 2006. Looking only at visible cases, it noted that “a treated dengue episode imposes a substantial expense on both the health sector and the overall economy.”

Making use of secondary data

Last July, we discussed a novel opportunity for examining the true burden of dengue: dengue vaccine trials.

A recent study published in the American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene made the best use of one such opportunity. “Resource Use and Costs of Dengue” analyzed data relating to 1,279 confirmed dengue cases in children gathered during two trials that were part of a dengue vaccine phase III efficacy study of more than 30,000 children aged between 2 and 16 years in which some of the children received the dengue vaccine.

“We evaluated the difference in dengue costs between vaccinated and not vaccinated children based on data gathered during a dengue vaccine efficiency trial,” said Laurent Coudeville, senior researcher at CRESGE (Université Catholique de Lille) and modeling director at Sanofi Pasteur. “Because of that, the children may have been treated a little differently to how they would have been treated in clinical trials.”

The trials took place across five countries in the Asia-Pacific region (Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam) and five countries in Latin America (Brazil, Colombia, Honduras, Mexico, and Puerto Rico). During the 25-month dengue surveillance period, both vaccinated and unvaccinated children contracted dengue: of the 901 confirmed cases of dengue among children aged nine years and above, just 373 of cases were in vaccinated children.

The trials took place across five countries in the Asia-Pacific region (Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam) and five countries in Latin America (Brazil, Colombia, Honduras, Mexico, and Puerto Rico). During the 25-month dengue surveillance period, both vaccinated and unvaccinated children contracted dengue: of the 901 confirmed cases of dengue among children aged nine years and above, just 373 of cases were in vaccinated children.

Beyond public costs

The report examined both the cost to public healthcare systems and the losses families suffered. After all, when a child catches dengue, they need an adult to look after them until they recover and that person will often need to give up work during that time.

To calculate average costs for both healthcare systems and families, it gathered information on:

• where the child received medical help

• how they got there – by ambulance, taxi, car, motorbike or public transport

• any consultations, examinations, medications or tests they received

• the school days they missed, and the days their caregivers missed from work

“We documented not just cost but also resource utilization: whether someone went to the hospital, how many consultations they had and whether someone had to stop working,” says Laurent.

These were then adapted to take account of the cost of living in the country where the child lived. “We adapted the costs based on each country, for example, how much one hospitalization day or one consultation would cost there,” says Laurent. “What you can get with a US dollar (US$) varies from one country to another so to be able to compare costs, we used the international dollar (I$), which aims to correct for that.”

The economic costs of dengue: what the study found

Of the 1,279 confirmed cases, 901 were in children aged between 9 and 16. In the 528 of the 901 cases where the child had not been vaccinated against dengue fever, the disease led to:

• 0.5 days in hospital at an average cost of 2014 I$147.79

• 2.5 consultations with an average total cost of 2014 I$168.70

• 2.2 missed school days

• 0.5 lost workdays for parents or carers with an average lost wage of I$88.01 (2014)

• I$4.30 in travel costs (2014)

In the remaining 373 cases, the child had been vaccinated against dengue. The disease resulted in:

• 0.3 days in hospital at an average cost of 2014 I$77.90

• 2.4 consultations with an average total cost of 2014 I$160.05

• 1.8 missed school days

• 0.5 lost workdays for parents or carers with an average lost wage of 2014 I$68.31

• I$4.07 in travel costs (2014)

The study confirmed the WHO view that “If a vaccine were able to prevent much of this burden, the economic gains would be substantial.” It found that for each dengue case, vaccination led to an average:

• 43% drop days in the hospital, reducing costs by an average 47%

• 4% drop in consultations, reducing costs by an average 5%

• 18% drop in missed school days

• 33% drop in lost workdays for parents or carers, reducing lost wages by an average 22%

• 5% drop in travel costs

The incidence of dengue was also lower in the vaccination group, further reducing overall costs to that group of children.

We want to hear about your experience with vaccine prevention tools. How successful were they in your fight against dengue?

—

Click below to report dengue in your area to Dengue Track.