- by Alison

Urbanization and globalization: spreading dengue around the globe

Half a century ago, dengue was under control; DDT and spraying kept Aedes aegypti mosquitoes at bay. In stark contrast, dengue is now a serious global health threat. Over the past four decades, dengue’s global threat has grown as urbanization and globalization have helped the Aedes aegypti mosquito spread the disease around the world.

We spoke with Professor Duane Gubler, Founding Director, Program in Emerging Infectious Diseases, Duke-NUS Medical School, Singapore, about the global trends over recent decades that have taken dengue from being a controlled disease to the growing global health problem we see today.

Complacency, urbanization, and globalization

Fifty years ago, every house in an affected area would be inspected for mosquito breeding and sprayed with DDT to eliminate the Aedes aegypti mosquito. It was a quick and cost-effective method for preventing outbreaks of dengue and other mosquito-borne diseases. Developed in the 1940s, DDT was the first modern synthetic insecticide. It could be sprayed both inside and outside of homes and other buildings, making it an ideal control tool.

“In the 1970s, we became complacent,” says Professor Gubler. “Dengue was not thought to be a global health problem. Interest in the disease decreased, along with the resources that went into managing it.”

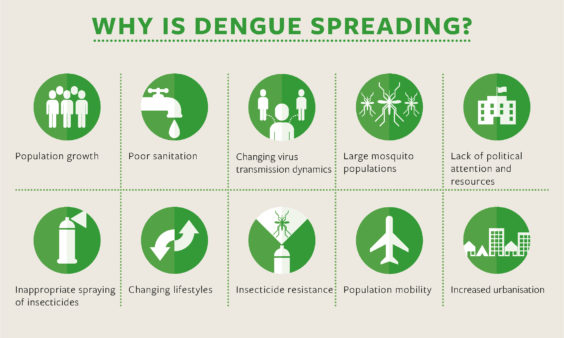

But it’s not only our complacency that has led to dengue’s global threat becoming what it is today. Urbanization has also had a major role to play. Cities have grown bigger over recent decades. With that, they’ve become overcrowded. Housing is poor. Water and waste management are inadequate. Cities are now an ideal habitat for Aedes mosquitoes to thrive.

“It’s difficult to inspect and treat every house in large overcrowded cities,” says Professor Gubler. “Over the years, spraying techniques have evolved to spraying small droplets of insecticide into the air and hoping they impact a flying or resting mosquito – rather than targeted spraying of surfaces where mosquitoes rest before and after feeding and egg laying.”

In addition, growing cities mean more people are traveling between them and surrounding rural communities. These travelers are helping the Aedes aegypti mosquito (which can only fly a few hundred meters under its own power) spread further afield.

Add to that globalization. Nowadays, we travel across the globe more than ever before – unsuspectingly introducing dengue viruses and Aedes aegypti to new regions of the world.

New solutions required

But it’s not just complacency, urbanization and globalization that have been helping the Aedes aegypti mosquito reach and establish itself in new locations. The mosquito has also built up resistance to DDT and the other insecticides that were keeping dengue under control.

“We desperately need a new insecticide, a new compound that can be sprayed both outdoors and indoors to control mosquito populations,” says Professor Gubler. “An insecticide that is safe and people can use themselves would be tremendous.”

A new insecticide solution will require multiple compounds that can be alternated to minimize the risk of the mosquitoes developing resistance. But developing new insecticides is an expensive process, increasing the economic risk for chemical companies and consequently, reducing the number of companies willing to invest their time and resources.

As such, partnerships are key to developing novel solutions since they reduce the risk for private sector companies but providing them with some of the resources needed. Private sector companies might establish partnerships with governments or charitable organizations, for example.

“The Gates Foundation has funded research at the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine to help move development of new insecticides forward,” says Professor Gubler. “There are new compounds under development.”

However, a sustainable approach to tackling dengue will need to go beyond controlling the Aedes aegypti mosquito; it will also require increasing people’s immunity to the disease itself.

“Vaccines are important,” says Professor Gubler. “They give us a critical new tool alongside new insecticides and novel solutions such as Wolbachia bacteria and friendly mosquitoes.”

While the Sanofi dengue vaccine is available today, there are a number of vaccines in development in the dengue vaccine pipeline from companies such as Takeda, Merck, and others.

Community action

With local government resources already stretched, Professor Gubler is keen to emphasize the role individuals have to play in tackling dengue: “No government has the resources to reach every house in our growing cities. Bringing the community into the process is key.”

He highlights the success of the community-based programs run by Rotary International in cities such as Manilla and Bangkok since the 1970s. “In 1998, Rotary International helped prevent a dengue outbreak in Purwokerto in Indonesia,” says Professor Gubler. “There were very few cases that year while neighboring cities suffered badly.”

The successful fight against dengue in Purwokerto involved partnerships between the local government, the Rotary Club, local communities and municipal health services – a then novel, approach documented in a World Health Organization case study. More recently, a community-based program in Nicaragua was also successful in reducing dengue transmission.

Sadly, community-based programs have not always had the impact expected, often because of a lack of support from local authorities. “Over the years, I have seen ministries of health fail to provide local communities with the expertise and guidance they need,” says Professor Gubler. “Fighting dengue requires a strong partnership between local authorities and local communities – and also NGOs, such as Rotary International.”

One thing is clear – we cannot afford to get complacent about dengue’s global threat again. Even with vaccines added to our toolbox, we must continue our efforts controlling mosquito populations.

As Professor Gubler says: “Urbanization and globalization mean the risk of dengue is now higher than ever before. While increasing dengue immunity is important, we must also continue to focus on decreasing mosquito populations.”

Tell us about the steps your community is taking to eliminate mosquitoes from your community and to stop dengue from spreading.

—

We are working with HealthMap to accurately predict dengue fever cases around the globe. Report dengue near you to Dengue Track.