- by Gary Finnegan

Dengue in Venezuela: How political instability is increasing risks to public health

Researchers studying the feasibility of introducing dengue vaccines to Venezuela and Colombia find a stark contrast between neighboring nations

Dengue in Venezuela is adding to the worries surrounding public health in the country. Around half, the 25 million people living in Colombia and 32 million in Venezuela are at risk of dengue fever. The two countries share a border, have the same climate and are of similar size. But their political and health systems are significantly different.

While Venezuela is gripped by a political crisis, Colombia is enjoying a period of relative stability. The situation in Venezuela is grave. Not only have there been violent clashes on the streets, but the economy is also collapsing – with severe implications for the health system.

Hospitals are at breaking point, doctors are working without pay, and vaccine-preventable diseases are making a come-back. The Americas were declared measles-free in 2016 but, as immunization systems disintegrate, the disease has promptly returned to Venezuela – spilling over into measles outbreaks in northern Brazil.

‘The political situation is worsening making it increasingly difficult to deal with dengue and other infectious diseases,’ says Dr. Aileen Chang, Assistant Professor of Medicine at George Washington University Medical School in Washington DC. ‘It’s almost impossible for doctors to care for patients and to do medical research.’

Dr. Chang has been working with partners in Venezuela and Colombia to survey patients, healthcare professionals, and health officials on the feasibility and acceptability of introducing a dengue vaccine. Her team won $10,000 through the Break Dengue Community Action Prize and will soon publish a paper on their findings.

The project was designed to test whether the two countries had the appetite and resources to introduce a vaccine program in endemic areas, like the dengue immunization program launched by Parana State in Brazil.

The study included 351 patients, 197 health professionals, and 26 government officials. The George Washington University Medical School designed the survey and analyzed the data.

Mixed fortunes

Dr. Chang’s work with partners in Barranquilla, Colombia, and Merida, Venezuela, illustrated the mixed fortunes of two neighboring countries where dengue remains a threat. In Colombia, respondents view dengue as a moderate-severe problem and said that a dengue vaccine would be useful in their communities. Most survey participants believe that their current vaccination programs can handle the addition of a new vaccine.

‘The general view in Colombia, where a number of outbreaks have been reported recently, is that the system could roll out a dengue vaccine and that it might be welcomed in areas where the diseases are endemic,’ she says.

In contrast, respondents in Venezuela did not view dengue as their biggest current concern. ‘With the breakdown of infrastructure, they pointed to logistical challenges associated with administering vaccines and maintaining the cold-chain,’ says Dr. Chang.

‘What’s really heartbreaking is that there is so much arboviral disease resurging in Venezuela because of the lack of mosquito-control. It highlights that healthcare infrastructure is crucial to controlling dengue fever.’

Conducting the survey was itself a challenge for researchers on the ground. Dr. Chang’s partners in Venezuela ran out of paper and could not print the surveys. Instead, they used tablets and cell phones to collect data and uploaded them to an online database – when internet access allowed.

Even leading teaching hospitals are struggling to deliver basic care to patients in need. ‘Many of our partners conduct research and provide care but are struggling to do either,’ said Dr. Chang. ‘One of our contacts described how, due to lack of resources to buy hospital supplies, they had just one glove for examining and treating patients. This single glove is washed after used and worn again when examining the next patient.’

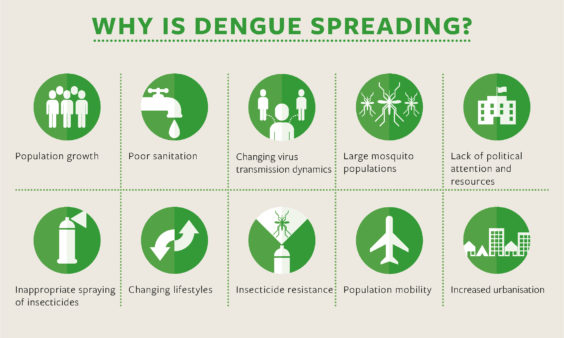

Image courtesy of Malaria Consortium

A fund-raising campaign was recently launched to help health professionals in Venezuela provide basic care.

New projects

This is not the only dengue-related project Dr. Chang is working on. Her team is collaborating with partners to study how the introduction of Dengvaxia – the only licensed vaccine currently available – would impact on dengue hospitalized rates.

She is also examining the role of non-structural protein 1 (NS1) in causing severe dengue. ‘NS1 appears to be related to vascular permeability syndrome which causes the vast majority of morbidity and mortality in dengue,’ Dr. Chang explains. ‘We are doing a translation study to evaluate NS1 concentrations in patients with mild, moderate and severe dengue to see if those levels differ depending on whether you have had a previous infection with a dengue virus.’

Sign the petition for an official World Dengue Day

In addition, the team hopes to explore the potential of an existing influenza medication for treating vascular permeability in dengue patients. ‘We are seeking funding to repurpose an antiviral influenza medication which has been shown in the lab and in animal studies to inhibit enzymes that break down the vascular endothelium,’ Dr. Chang says. ‘If successful in human studies, this existing flu medication could be used in the fight against dengue.’

With dengue now accepted as a major public health concern, Dr. Chang and partners are playing their part in providing multi-faceted approaches to curbing the burden of dengue fever. If her survey is anything to go by, tackling dengue will take a combination of cutting-edge science and political support.

—

Sharing local dengue activity can give health experts a clearer picture of this disease. If you’re experiencing dengue near you, report it to Dengue Track below.