- by Alison

Dengue disasters: why storms and earthquakes boost mosquito populations and risks

Hurricanes, earthquakes, tsunamis, typhoons and other natural disasters continue to claim their victims long after they strike. Weeks and even months after their initial devastation, disaster-hit areas face a rise in cases of dengue fever and other vector-borne diseases. With a series of natural disasters fresh in our minds, let’s take a closer look at the link between hurricanes, earthquakes, and potential dengue disasters.

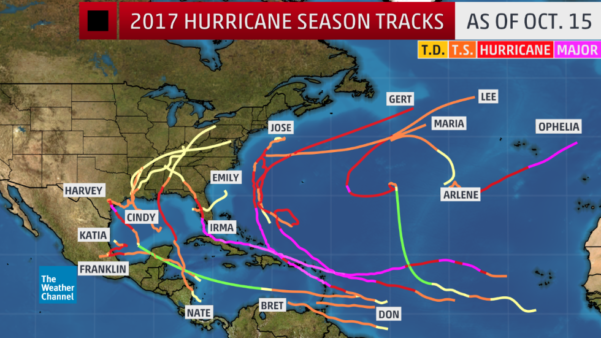

While Atlantic storms hit the Americas between May and November every year, the 2017 season was particularly devastating. Between mid-August and early October, Hurricanes Harvey, Irma and then Maria brought winds strong enough to knock down trees and tear buildings apart.

Image via weather.com

After Hurricane Harvey battered Southern Texas, Hurricane Irma hit the Caribbean then made its way north towards Florida. Not long afterward, Hurricane Maria took a second swipe at the Caribbean before heading north west.

Dengue disaster: devastation across Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico’s fragile infrastructure was particularly badly damaged. An article in the New England Journal of Medicine notes, “As of 16 days after the hurricane, 25 hospitals were working, only 9.2% of people had power, 54% had water, 45% had cell phone service.”

We spoke with Dr. Dawn Wesson, associate professor at the Tulane University School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine. She explains why the hurricane has led to an increased risk of dengue, “There are problems with electricity and lack of access to clean water in Puerto Rico. Any opportunity they get, people are storing water. When you start storing water, Aedes aegypti start breeding, and their population increases.”

The New England Journal of Medicine article confirms: “The potential development of infectious disease outbreaks and reactivation of dengue, Zika, and chikungunya epidemics is one major concern… This hurricane might well increase the mosquito population, and people may not pay attention to prevention messages or be willing to modify behaviors that affect their seeking of food, water, and gasoline or repairing of their homes.”

With hospitals and roads closed, keeping transmission at bay and keeping track of disease is all the more difficult – whether water-borne, food-borne or mosquito-borne. Cases of water-borne leptospirosis, for instance, appear to be on the rise.

“There is such as lack of infrastructure right now that, unless someone was really ill, they probably wouldn’t attempt to get to a hospital,” says Dr. Wesson. “That could increase the risk of disease transmission to others.”

Mexico hit hard too

During September, the Americas faced yet another natural disaster: on the 19th an earthquake with an estimated magnitude of 7.1 hit Central Mexico. More than 40 buildings collapsed, 370 people were killed and more than 6,000 were injured. This earthquake followed an 8.2 magnitude earthquake in southern Mexico less than two weeks earlier.

Image vie @latimesgraphics

Earthquakes, like hurricanes, increase the risk of dengue outbreaks. People are displaced from their homes or no longer have access to running water. “When people have to store water, the potential for Aedes aegypti populations growing increases exponentially,” says Dr. Wesson.

According to Mexico News Daily article from 6th October: “About 4 million people lost their water supply after the [September 19th] quake.”

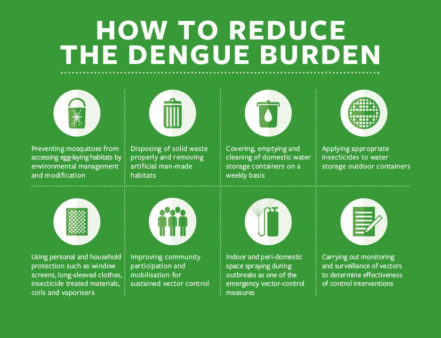

Officials acted quickly to mitigate the risk of dengue outbreaks after the earthquakes in Mexico. The state government office in the Morelos region near to the epicenter advised on its @GobiernoMorelos Twitter account: “We are reminding people to take preventive measures to take care of the health after the earthquake in #Morelos”.

Preventative measures aimed at avoiding an increase of insect-transmitted diseases such as dengue, chikungunya, and Zika, according to an article in The News, included “buckets, washbasins, water tanks, cisterns, vases and any container that [is] used to store water should be properly covered.”

Image courtesy of Malaria Consortium

Dengue spike after Padang earthquake

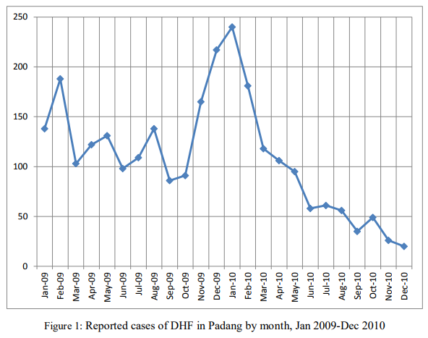

While it is still too early to know whether the Mexico earthquakes will lead to an increase in dengue, an earthquake that struck Padang, West Sumatra on September 30th, 2009 did: the number of reported cases of severe dengue spiked in late 2009, almost immediately following the earthquake.

Image via International Journal of Collaborative Research on Internal Medicine & Public Health

More than that, study author David Fanany from La Trobe University, Bundoora, VIC, Australia noted why the earthquake increased the risk of dengue in his paper Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever and Natural Disaster: The Case of Padang, West Sumatra. “While dengue is a chronic problem in this area, the earthquake created a set of factors that enhanced transmission of the disease and also led to a set of circumstances in which prevention was unusually difficult.”

The Padang earthquake caused significant damage to government, commercial and residential buildings, many of which were abandoned in the following months. Cleanup of earthquake rubble was at best slow; the departed owners of abandoned sites were left to clear their properties up.

Damage from the 2009 Padang earthquake. Indonesia 2009. Photo via AusAID

As in Mexico, the earthquake also disrupted water supplies, leading residents to collect rainwater and store large amounts of water around their homes.

While the change in the living environment increased viable breeding locations for mosquitoes, the timing of the earthquake increased their capacity to breed: the earthquake occurred at the beginning of the rainy season. Mosquito activity increased along with contact between humans and mosquitoes.

Dr. Wesson also emphasized the importance of geography and timing when she spoke with us: “Hurricane Sandy hit the North West of the US late in the season a couple of years ago, but the region didn’t experience any mosquito-borne disease problems in the aftermath.”

Preventing dengue

Improving infrastructure is one of the critical factors when it comes to reducing the impact of natural disasters – from all perspectives. If buildings can withstand natural disasters, lives will be saved. Furthermore, people will not be made homeless and exposed to the elements and disease-carrying insects. If water supplies can be maintained, people will not need to store water.

Robust infrastructure is, therefore, vital for reducing the risk of dengue following earthquakes, hurricanes, and other natural disasters. Take Southern Texas as an example. Solid infrastructure meant the impact of Hurricane Harvey on utilities was less significant. People there, however, still faced an increased risk of dengue: out rebuilding their homes, they were more exposed to the Aedes aegypti mosquito.

Some of the newer vector control technologies, including Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes and sterilized male mosquitoes, could also play a role. As the Miami Herald reports, the US Department of Agriculture recent eliminated the deadly American screwworm fly from the Florida Keys by releasing hundreds of thousands of sterile flies over a six-month period.

“If you could quickly bring in sterile males or the Wolbachia-infected insects, that would improve your capacity to respond to the dengue threat after a hurricane, earthquake or another natural disaster,” says Dr. Wesson. “It would be another nice thing to have in your toolbox to fight dengue.”

Dengue vaccination could also play a key role in minimizing the risks of infection in the aftermath of a natural disaster. “If a population was already vaccinated against dengue, you would be less concerned in a situation like Puerto Rico.”

We want to hear your stories. How is your community taking the fight to dengue?

—

Add your VOICE for a Global Dengue Day and sign the Open Letter to the United Nations General Assembly.

https://www.breakdengue.org/global-dengue-day/