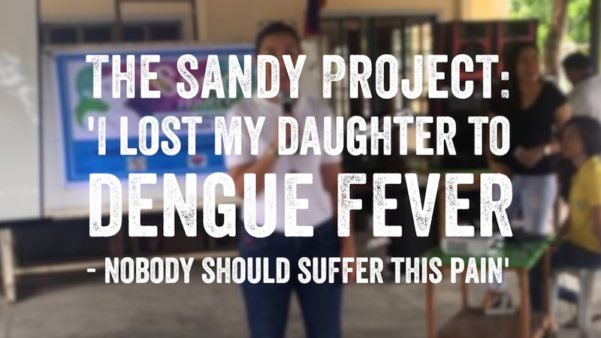

The Sandy Project draws from her intense pain from her own loss. Peaches Aranas reaches out to communities in the Philippines so that no mother will lose her child to dengue again.

It was February 2013 when my only daughter Sandy caught dengue and unexpectedly passed away seven days later. She was only 10 years old. She had the disease for just seven days! We detected it early and she was hospitalized on day two of her fever. We were in the best hospital and had the best medical care. And yet, we still lost her.

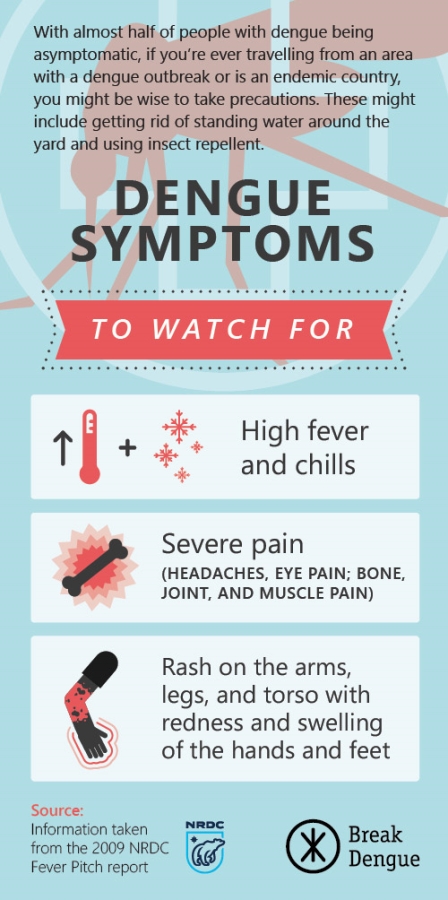

Four years later, I feel like I have not even touched the surface of the pain of losing my daughter. I told myself, ‘I have to do something.’ Imagine, one second was all it took. One second for that mosquito to infect my daughter, for me to lose her. That realization is not easy. One second changed our lives forever. That’s how dangerous dengue is, and yet we took it for granted, and so many still do not take it seriously. Don’t think it can’t happen to you.

Losing her changed me. There is a black hole that’s too deep, I don’t even know its bottom. There are an emptiness and a longing that is choking and suffocating. But every day, the sun rises and I can’t stop it. The rays are bright and beautiful and shine on my emptiness. I just learned to see that and appreciate it for what it is, a ray of hope.

This is a tragedy I had vowed no other parent or child should suffer, so later that year, I launched, “The Sandy Project.”

It’s a self-funded advocacy initiative that I hope will help bring down the dengue menace and bring honor to the memory of my unica hija.

Dengue in Davao: Zarah went to the Philippines for work and wound up in hospital

When she passed away, it really broke our hearts and broke our whole family. We didn’t know what hit us. So as a way to cope, I thought of doing something to leave a legacy for Sandy, so her life would not have been for naught.

The Sandy Project is a gift that I want to give to fathers, mothers, and siblings who can lose a loved one to dengue.

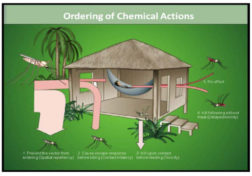

Together with partners from the public and private sector, the Sandy Project goes to schools and localities and educates children and parents on the importance of preventing and protecting against the deadly dengue virus.

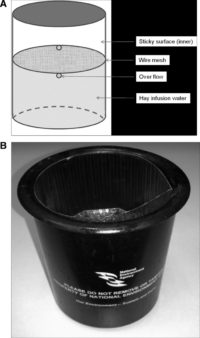

The campaign provides children and its beneficiaries with anti-mosquito sprays and lotions, mosquito nets and other anti-insect medicine and equipment, and teaches children about dengue through games, songs, dances, and books that are also given away to communities to aid their dengue education efforts. Just recently, we came out with a book, slippers, and a Dengue NS1 test kit to give away.

The campaign has a dual focus – an awareness component and a prevention component. The book came about to address the awareness component. It is a poem where a little girl named Sandy talks about what could have been if she were water, fire, wind, or earth. It goes on with the little girl talking about herself, about dengue, and about the power of many kids put together to defeat dengue. The book seeks to address the (dengue) awareness part of the campaign.

The slippers and the (dengue) test kit seek to address the prevention part of the campaign. Every morning, when the children wake up and put on their slippers, they will be reminded of The Sandy Project and Sandy. The slippers have button pins with a picture of the logo of The Sandy Project or of a scary-looking mosquito or an anti-dengue button. This will remind them to check their surroundings for stagnant water. Every time they put on the slippers, it serves as a reminder to them.

The test kit is to give them an early and easy way of checking if they have dengue. They don’t need to go to the hospital and wait so long. They won’t also need to pay so much. With the home test kit, which I plan to give to the health centers, early detection is possible.

I share Sandy’s life story and our horrible weeklong experience of fighting this virus with the children, in the hope that they will crusade with me in fighting dengue and saving lives.

I hope I can reach 5,000 kids a year. That’s the amount I can afford, out of my own pocket, even without donors. It is also our family’s gift to Sandy to honor her short life with a legacy that speaks of purpose and hope. And it is my humble gift to God, in thanksgiving, for the blessing of 10 years with a beautiful daughter. It is a reminder that we are but stewards of this earth.

Has doing this helped in coping with my daughter’s loss? I’m not sure. To be honest, I don’t even know if I am coping. I haven’t reached the bottom of my pain. I think I’m only at the surface.

What I do know is that losing Sandy is not an experience I wish even on my worst enemy.

To all the parents out there, you are so blessed if you can still touch and embrace your children. You are so blessed if you can watch them grow up. Right before your very eyes, you witness the changes in them, the way they are, their thoughts, interests, and passions. I really wish I could do the same. I really wish I can have new experiences, memories, and pictures of and with Sandy.

Dengue is different: why the dengue vaccine is still needed

The truth is, because of dengue, I will never have another day with her.

—

Click below to learn more about dengue fever and how to prevent it.

The Denvaxia rollout continues as more countries around the globe approve

The Denvaxia rollout continues as more countries around the globe approve