- by KRIZETTE CHU

Vector control technology: A look at the tools stopping the mosquitoes that spread dengue

MANILA, PHILIPPINES—At last month’s second Asia Dengue Summit in Manila, top infectious disease experts from the region met with government officials and public health stakeholders to discuss the increasing burden of dengue and the advances in science and technology that may help combat the spread of the disease. Vector control technology was high on the list.

Dr. Grace Yap, a senior research scientist and program head for the National Environmental Agency’s Environmental Health Institute, shared how technology has helped her home country of Singapore fight the disease. In Asia, Singapore has the most advanced technologies in vector control, and at the core of their strategy is source reduction and environmental management.

Globally, current transmission control relies mainly on insecticide sprays, which are plagued by many issues including insecticide resistance and toxicity.

Here is how Asia, particularly Singapore, has been trying to improve current tools and advancing the development of products that will help with vector control.

Genetic control

Called Project Wolbachia, Singapore’s six-month study involves the release of male Wolbachia-carrying Aedes aegypti mosquitoes to help suppress the population of urban Aedes aegypti.

Eggs produced from the male Wolbachia-infected Aedes aegypti mosquito and a female urban Aedes aegypti mosquito will not hatch due to incompatible matching.

While the male mosquitoes may fly around and enter homes to seek out females and find shelter, they will not bite or transmit disease.

Since October 2016, the male Wolbachia bacteria-carrying Aedes aegypti mosquitoes have been released on a regular basis at three selected sites.

The viability of Aedes aegypti mosquito eggs collected from a site at Tampines West has been reduced by about half.

Read how Oxitec’s ‘friendly mosquitoes’ are protecting thousands from dengue

85-92 percent of households have no objections to releasing male Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes. Says, Dr. Tan, “The NEA has found that the use of male Wolbachia is promising, but cannot be the sole strategy of Aedes control. It must be complemented with a strong integrated control program with strong community participation.”

Intelligent Gravitrap

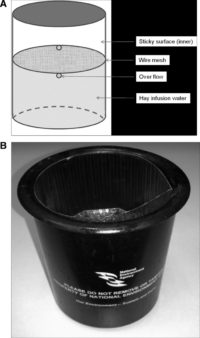

Schematic design (A) and picture (B) of Environmental Health Institute, Singapore, sticky Gravitrap. Image via The American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene

Singapore’s Environmental Health Institute developed Gravitraps, designed to lure and trap gravid female Aedes with a sticky lining. The traps exploit the behavior of female Aedes aegypti, who distributes her eggs in multiple containers during each cycle, a behavior that increases the survival of her young.

The Gravitrap is simple and cheap to make and is made of a black container containing 10 percent hay infusion and an inner shorter cylinder lined with adhesive glue to trap gravid females searching for oviposition sites. The smaller inner cylinder is fitted with a wire net base, which sits above two holes punctured through the outer container to prevent the emergence of adult mosquitoes just in case eggs are laid before females are trapped.

It is important that the design is simple and failsafe, so it can be used by ordinary people, an approach consistent with Singapore’s advocacy for community participation. Currently, a chemical lure is under development to replace the hay infusion water to enable its wide and regular use by the community to prevent dengue transmission.

Spatial repellents

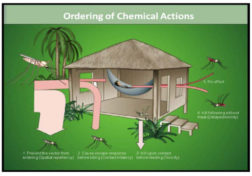

Image showing how spatial repellents work via BioMed Central

Spatial or area repellents (pyrethroids) are chemicals that “work in the vapor phase” to prevent mosquitoes biting humans by disrupting their behavior within a certain area. The benefit of spatial repellents is that unlike regular insecticide sprays, it can be applied to specific areas both indoors and outdoors.

Volatile chemicals at ambient temperatures are used. When these chemicals are applied, they can “repel” rather than kill mosquitoes. Chemicals used include transfluthrin.

Big data analytics

In the Philippines, big data analysis helped a Singapore-based IT expert to track dengue incidences in his home province of Pangasinan when he pored through figures that pointed to a certain school that reported the most cases. Looking at his district’s topography, Wilson Chua detected catch basins around the area during rainfall and found out there were deeper areas where rainfall could possibly stagnate.Having identified these places, Chua then bought from Singapore mosquito dunks that contained BTI, a bacterium that kills mosquitoes and their eggs, and spread it in these areas, which greatly reduced dengue in the area.

Having identified these places, Chua then bought from Singapore mosquito dunks that contained BTI, a bacterium that kills mosquitoes and their eggs, and spread it in these areas, which greatly reduced dengue in the area.

In Singapore, experts use meteorological services—from climate data, temperature, absolute humidity—to see how the weather in coming days may affect the spread of the illness. It is supplemented with information on house index, breeding index, and population data to create a three-month real time dengue forecast model. Armed with early warnings of outbreaks, the Singaporean government’s EHP can now craft long-term strategies and public health response to avoid impending outbreaks.

Regional surveillance

In a highly mobile world, collaboration among neighboring states is highly essential—and in Asia, Singapore leads the way with the creation of an organization founded by Singapore’s NEA, Malaysia’s Ministry of Health, and Indonesia’s Andalas University. The network has expanded to 10 countries that include Sri Lanka, Brunei, Pakistan, Laos, Thailand, and Vietnam. Through such cross-border collaboration and sharing of dengue information, timely sensing of the dengue situation can improve preparedness within each country in the event of an outbreak.

Centers and laboratories of these countries stay in close contact with each other, and the World Health Organization shows its support by providing technical and financial support to manage dengue. In pooling their resources together, these countries hope to avert or lessen dengue in the region that is most hit by dengue.

Looking ahead

Until the development of Dengvaxia, the world’s first dengue vaccine, there were no clinical preventive measures available to healthcare professionals. Classified as “moderately” effective, the vaccine nevertheless prevents eight out of ten dengue hospitalizations, and nine out of 10 severe dengue cases.

The vaccine’s arrival in the market, much anticipated after 20 years of intensive research, is perhaps the most encouraging indication that we could keep up with dengue. “Control is possible if we combine vaccines with best vector control tools,” says Dr. Hasitha Tissera, a medical epidemiologist leading the National Dengue Control Program of the Ministry of Health in Sri Lanka. “To completely combat dengue, we need three things: Vector control, vaccinate, and surveillance. That is the way forward.”

—

Click below to report dengue activity in your area.