- by KRIZETTE CHU

Dengue disaster: Lessons from a tragedy

Debris line the streets of Tacloban, Leyte island following Typhoon Haiyan in 2013.

Experts are working together to curb dengue outbreaks after natural disasters

On November 8, 2013, Typhoon Haiyan hit the central provinces in the Philippines with a force that had never been seen before. The most commonly used satellite-based intensity scale showed that the typhoon was literally off-the-charts—registering at above 8.0.

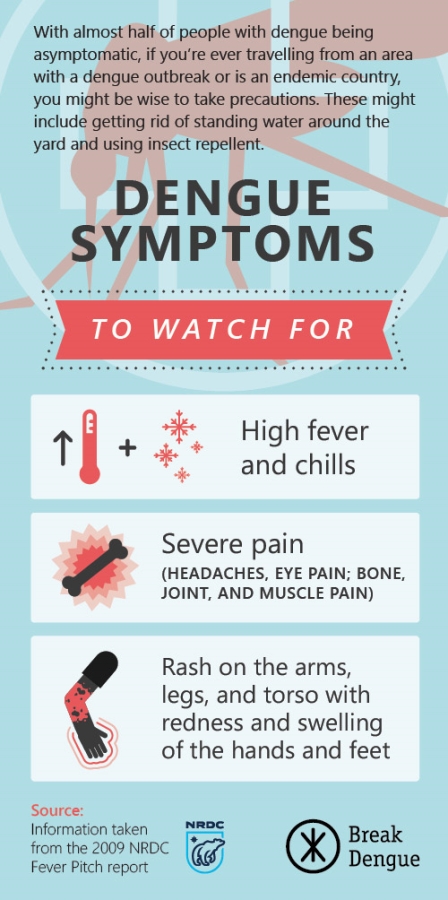

The Philippines is the most typhoon-ridden nation on Earth, walloped with an average of 20 typhoons a year. Add this, coupled with the fact that dengue is endemic in the country, is a recipe for disaster.

In the Philippines, dengue has become a year-round risk, but dengue outbreaks are particularly common after natural disasters such as earthquakes, typhoons, and floods.

Typhoon Haiyan rapidly destroyed houses, hospitals, and infrastructure on a massive scale, with worst-hit Leyte bearing the brunt. The rains that poured days after Haiyan struck Leyte contributed to the pooling of stagnant water that was trapped under debris, which caused a large increase in potential mosquito breeding sites.

In 2013, there were 3,200 cases of dengue. After Haiyan hit, the health authorities found a 61 percent increase in infections, driving the total to 5,200 cases in the two months after Haiyan.

At the 2nd Asia Dengue Summit in Manila last month, leading experts from all over the region gathered to swap notes and share best practices in the global fight against dengue. Leonido Olobia, program manager for dengue, malaria, and research at the Department of Health of Region 8, the region hit hardest by Haiyan, talked at length about how the region’s experts tried to cope with the challenges of a potential outbreak.

“Our aim was to prevent an outbreak in the immediate aftermath of the typhoon and to reinstate dengue control, surveillance, and response,” he says.

The WHO public health risk assessment for Typhoon Haiyan recognized dengue fever as one of the health priorities for the affected areas, with a potential increase in cases occurring in the next six weeks.

“We did the best we could given the circumstances,” Olobia said. “The team was faced with many challenges: We were short on personnel as the local staff has been affectedly greatly, and there was immense difficulty in coordinating operations among the local and international vector control teams. Around this time, communication lines were down.”

The department also had no control over local governments and city mayors, and funding was low. Olobia’s team had to quickly create a new system and a multifaceted response was swiftly set up. To address the lack of funding, the Department of Health (DOH) tapped the help of international agencies to sponsor salaries of civilian emergency workers on a Cash-for-Work program for vector control operations in Tacloban, the capital city.

Additional health personnel from the DOH and foreign medical teams worked on surveillance reporting. Vector control operations were stepped up: Fogging, larviciding (applying a chemical on stagnant water), and search-and-destroy activities happened 12 days after Haiyan and were conducted in areas around hospitals, damaged schools, evacuation centers, and other public areas.

Help had to be sourced through staff from other regions and foreign medical teams who continued to stream in to offer their help. Sanitation teams, as well as communities, were quickly trained in vector control, with the DOH promoting search-and-destroy activities with the support of the civilian brigades.

The government worked double-time to ensure garbage collection in hard-hit areas to reduce mosquitoes and flies, which was important due to the continuous rainfall in the months following Haiyan.

Runners with motorbikes—the debris has not been cleared and cars could not pass through most roads—were hired to collect data and submit them to the provincial level, which in turn were turned over to the national and regional offices. Dengue case maps were continually updated, shared among coordinators and program managers at meetings among stakeholders.

Four weeks after the typhoon, commercial dengue rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) were distributed to eight hospitals and health centers, with positive cases reported to the authorities to guide response and targeted interventions.

As very few hospitals were operational (with most of them badly damaged), health experts conducted refresher training of health staff in both hospitals and rural health centers. Long-lasting insecticide-treated nets were distributed to government hospitals to prevent transmission to patients.

Assessments continued to be done by the WHO and regional health authorities three months after the typhoon. Three cycles of vector control were administered within two-week intervals in the places that were hardest hit.

The DOH and WHO launched awareness campaigns through radio programs, and foreigners were given instructions about how to deal with dengue, as many of them were also victimized.

Through strengthening dengue surveillance for early detection, targeted vector control, close collaboration with the community, and with the help of the international community, the worst possible scenario—a dengue outbreak in what is already a massively damaged and struggling community—was averted.

Olobia says, “We were faced with an overwhelming situation that threatened to escalate into a huge problem, and what we learned will benefit the country both in emergency and non-emergency responses in the future.”

—