Painted wall near Mexico City instructs residents about dengue. Photo courtesy of Professor Eduardo Undurraga.

We don’t yet have a clear picture of the true burden of dengue. It could be 58 million cases a year. It could be double that number. It could be half that number. We just don’t know. But understanding the true burden of the disease is critical – both for developing local dengue control and prevention strategies and for encouraging investment in technologies to help the global fight against the disease.

For dengue, as with all reportable diseases, public health systems are only able to report the cases that come to their attention – an approach to monitoring cases known as passive surveillance.

“Reported dengue case numbers depend on patients going to a health facility, those patients being diagnosed either clinically or through laboratory tests, and the healthcare providers reporting those cases to health authorities,” says Donald Shepard, Professor at the Schneider Institutes for Health Policy at Brandeis University in Massachusetts.

While those reported numbers are invaluable for public health– for comparing dengue over time and guiding responses – they aren’t always enough. When public health authorities are making decisions about deploying dengue prevention and control interventions, they need to understand the true burden of dengue. Professor Shepard explains: “To know the health benefits of a dengue control measure, you need an accurate picture of case numbers. With every dengue case avoided, the health system usually saves costs, and the well-being of the person who would otherwise have been sick is preserved.”

A true picture isn’t easy to come by

But figuring out the true number of dengue cases across a country is both time-consuming and costly. It requires active surveillance – where the health system carefully gathers information on the illnesses experienced by people across the country. Active surveillance for every case for every disease would be an extraordinary effort for a health system and a huge burden for patients.

“An extreme version of active surveillance throughout a country would literally require the country’s health system to telephone or visit every resident every week to ask if they had been ill in the last week,” says Professor Shepard. “If they had been ill, they would be asked to attend a clinic where they would give a sample of blood for testing. That would clearly be infeasible on a national level.”

Building a clearer picture

One answer to understanding the true burden of dengue lies in comparing existing passive surveillance data with data from any active surveillance undertaken in the same region. By doing this can you understand what percentage of dengue cases are reported and, from that, have a more accurate estimate of the true burden of the disease.

Take the Philippines as an example, where the government needed reliable estimates to inform dengue control measures. In 2012, the Armed Forces Research Institute of Medical Sciences (AFRIMS) and the Philippines AFRIMS Virology Research Unit (PAVRU), hosting Prof. Shepard and colleagues, described their ongoing cohort study on dengue in 1,008 adults and children in the Punta Princesa area of Cebu City in the Philippines.

Professor Shepard (front center) and other dengue experts meet in Cebu, Philippines, 2012.

The teams concluded that collaboration on a related study would be a valuable scientific contribution and feasible to implement. Subsequently, the related study was initiated with Professor Shepard as the principal investigator. Its goal was to estimate the burden of dengue in the Philippines using the active surveillance data gathered during the first study.

Professor Shepard explains: “We compared the active surveillance data of dengue infections from the Punta Princesa study with reported dengue episodes based on passive surveillance data from the Cebu City Health Department (CCHD).”

The study found the reporting rate of dengue in Cebu City to be just 21% or, expressed another way, the expansion factor of dengue to be 4.7. In essence, for every dengue case reported, there were between four and five actual cases.

Active surveillance from trials

Dengue vaccine trials provide another opportunity for gathering active surveillance data. Whenever a company tests a dengue vaccine or drug, it needs to capture and very precisely describe each illness to measure the effectiveness of its product.

A study into symptomatic dengue in five southeast Asian countries used the active surveillance data from Sanofi Pasteur’s vaccine trials to establish the dengue expansion factors for Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, the Philippines, and Vietnam. The study found it ranged from 0.5 to 31.7.

“Expansion factors vary from country to country, within a country, and may also vary by year,” says Professor Shepard. “The more active surveillance data becomes available, the greater our understanding of what the expansion factors are and how they vary.”

Read more: Building the ultimate dengue surveillance tool

There are also other ways to estimate expansion factors. They can, for instance, also be estimated by analyzing overlap between two independent samples of dengue cases using a technique known as ‘capture-recapture’.

But many countries have no active surveillance data nor independent samples. They can only make generalizations on expansion factors from neighboring countries. And even when countries do have data available, it’s generally limited; they have to make generalizations on expansion rates across regions.

Turning up the volume on dengue

Reporting rates and expansion factors also have another role to play: they’re helping the world understand how devastating the global of dengue is.

The GBD (global burden of disease) collaborators at the University of Washington publish estimates on the burden of hundreds of diseases worldwide – including dengue. “As better data have become available, GBD estimates on the numbers of dengue deaths and cases have been rising steadily,” says Professor Shepard.

Camino Verde (Green Way) participants exhibit mural near Acapulco, Mexico. Photo courtesy of Professor Eduardo Undurraga.

The rising estimates have helped to strengthen interest and investment in new approaches and technologies for fighting the dengue. Companies, governments, and donors are committing more time, money and resources.

But considerable uncertainty remains around current estimates. Professor Shepard discusses the figures he shared when we spoke with him last year on estimating the true cost of dengue: “We estimated 58 million annual episodes of dengue at a global annual cost of $8,9 billion. But economists’ confidence around that number is quite wide: the minimum could be less than half, or the maximum could be more than twice that number.”

Active surveillance is key to improving estimates not only on the burden of dengue but also on other diseases. After all, many of the uncertainties about the burden of dengue also apply to Zika since the same mosquito transmits both diseases.

“With Zika there is even less information on infections and, as such, even more, uncertainty. Applying what we have learned about dengue can help us understand the burden of and develop control strategies for other public health threats – in particular, the other diseases spread by the same species of mosquito, such as Zika and Chikungunya,” concludes Professor Shepard.

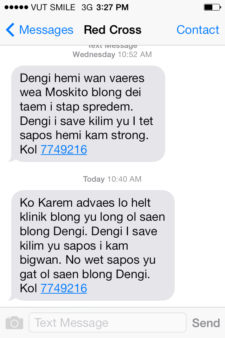

With many cases of dengue and Zika remaining undiagnosed, modern crowdsourcing tools are adding to the picture by allowing individuals to report cases themselves. Dengue Track, for example, combines information on dengue cases reported by users with statistics from larger national databases to create a real-time map of outbreaks and provide information to travelers, organizations and local communities. The same tool could be just as effective in mapping other mosquito-borne diseases, turning big data into actionable information.

—

The more data we collect, the more accurate the system will be. Report dengue activity to near you to Dengue Track.

During the wet season, the team visits monthly; during the dry season, they visit once or twice throughout the season.

During the wet season, the team visits monthly; during the dry season, they visit once or twice throughout the season.

Nicolás and his collaborators found that the mosquito that spreads dengue (Aedes aegypti) tends not to travel far. In fact, research suggests that, in cities, they only travel about 20m to 40m – around the length of a city block. He believes that the reason could be that mosquito might not be as competitive as would be outside the urban environment.

Nicolás and his collaborators found that the mosquito that spreads dengue (Aedes aegypti) tends not to travel far. In fact, research suggests that, in cities, they only travel about 20m to 40m – around the length of a city block. He believes that the reason could be that mosquito might not be as competitive as would be outside the urban environment.

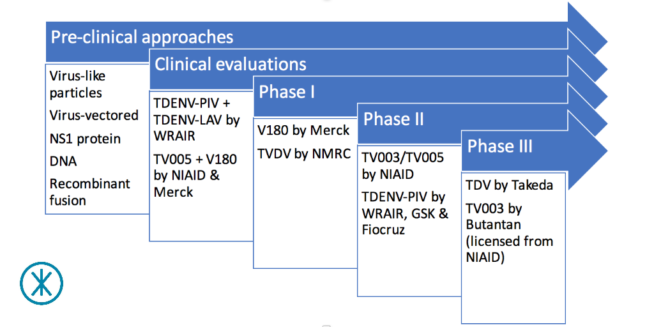

The dengue vaccine pipeline continues to develop steadily. We last took a look at the state of

The dengue vaccine pipeline continues to develop steadily. We last took a look at the state of  ay.

ay.

Aaron Hoyles is Program Manager of Break Dengue, a collective impact partnership initiative at The Synergist. Prior to joining The Synergist, Aaron worked as a management consultant for organizations of all sizes, including Allstate in the U.S. and startup Hub-Grade in France. Aaron began his career in the U.S. Navy. Aaron has a BA in Philosophy from DePaul University in the U.S. and an MBA in International Business from EMLYON Business School in France.

Aaron Hoyles is Program Manager of Break Dengue, a collective impact partnership initiative at The Synergist. Prior to joining The Synergist, Aaron worked as a management consultant for organizations of all sizes, including Allstate in the U.S. and startup Hub-Grade in France. Aaron began his career in the U.S. Navy. Aaron has a BA in Philosophy from DePaul University in the U.S. and an MBA in International Business from EMLYON Business School in France. Lode Dewulf is a physician with a passion for patient perspectives and understanding. When he studied and practiced medicine in Belgium and South Africa, he quickly realized that good education about health and disease was at least as important as good medicines to help patients achieve the best outcomes. To have a broader impact he then joined the pharmaceutical industry in 1989 and worked to provide education surrounding certain diseases and new treatment options. Ten years later, when the internet opened new possibilities to provide quality medical information, he took a one-year sabbatical leave to co-found PlanetMedica, the first Healthcare internet portal in Europe. He now has almost 25 years of pharmaceutical medical experience around the world and currently works as Chief Patient Affairs Officer at UCB, Belgium.

Lode Dewulf is a physician with a passion for patient perspectives and understanding. When he studied and practiced medicine in Belgium and South Africa, he quickly realized that good education about health and disease was at least as important as good medicines to help patients achieve the best outcomes. To have a broader impact he then joined the pharmaceutical industry in 1989 and worked to provide education surrounding certain diseases and new treatment options. Ten years later, when the internet opened new possibilities to provide quality medical information, he took a one-year sabbatical leave to co-found PlanetMedica, the first Healthcare internet portal in Europe. He now has almost 25 years of pharmaceutical medical experience around the world and currently works as Chief Patient Affairs Officer at UCB, Belgium.