- by Gary Finnegan

Vaccine confidence is key to beating dengue

A global expert in vaccine confidence says attitudes to other vaccines can affect dengue vaccination rates. Media monitoring and can help address fears and dispel myths.

Vaccines are among the top public health inventions of all time. Over the past 50 years, they have eradicated smallpox, pushed polio to the brink of extinction and helped to dramatically reduce childhood mortality.

It’s not just kids that have benefited. Vaccines against flu, meningitis, pneumonia and cervical cancer are protecting people of all ages against infectious diseases.

And yet vaccine confidence cannot be taken for granted.

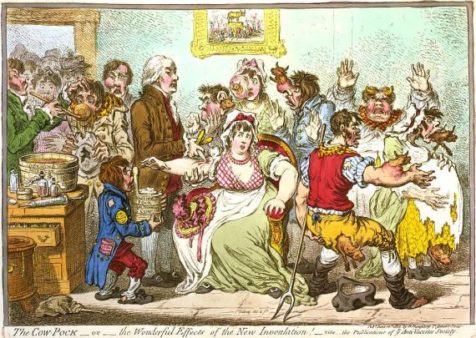

When Edward Jenner developed the first smallpox vaccine in 1796, people freaked out. They imagined that the material Jenner sourced from a cow to create the vaccine would cause them to grow udders.

But those were less enlightened times. Vaccines proved to be a public health wonder and are now universally accepted. Right?

Not quite. While more people than ever are now vaccinated (thanks to childhood immunisation campaigns) against potentially lethal infectious diseases, there is still plenty of work to do to convince some segments of the public of the value of vaccines.

And, as the 1990s MMR vaccine controversy showed, the combination of flawed science and careless media reporting can make anti-vaccine rumors go viral – sparking outbreaks of preventable disease.

Vaccine confidence studies

So where are we today? A survey of 67 countries found that while most people have a positive view of vaccination, there are still those with lower levels of vaccine confidence. (France – birthplace of Louis Pasteur himself – was the worst!)

Image: The Cow-Pock-or-the Wonderful Effects of the New Inoculation

The study was run by Dr. Heidi Larson of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. Larson runs the Vaccine Confidence Project and is a renowned expert in how people view vaccines. She says that people’s views on new vaccines are heavily influenced by their opinion on vaccines in general.

This means that when a dengue vaccine is being introduced, not only do health authorities have to deal with practical questions about how the vaccine will be transported, stored and delivered, they have to find a way to ensure that public confidence is not shaken by misplaced concerns based on rumors and myths.

That’s why a new dengue vaccination toolkit on how to introduce dengue vaccines includes a module on rumor management and communication. It’s no use having the vaccines, syringes and health professionals if public demand is low.

Introducing new vaccines

“We have to more homework when introducing a vaccine,” says Larson. “We can be so focused on the specifics of getting rolling out the vaccine itself that we don’t always look at what’s the uptake of other vaccines.”

Trust in science, public health authorities or government can affect vaccine uptake. For example, a crisis in food safety can spill-over into anti-vaccine sentiment.

“China faced a huge scandal with tainted milk which created general mistrust,” says Larson. “Then last year a story broke about a pharmacist who had been repackaging vaccines just as their expiry dates approached – it wasn’t directly to do with vaccines but it undermined the whole system.”

Even the MMR crisis that began in the UK came hot on the heels of a food safety scare where the public felt they had not been given the truth early enough. “We’ve got to lift our heads and scan the whole environment to assess trust in authorities and any other uncertainties that might be in the picture,” she says. “That’s why it’s unwise to launch a vaccine during an election. There’s a risk that it could get caught up in other political issues.”

Some countries, notably those in Scandinavia, have strong and interactive relationships with their publics, resulting in robust levels of public trust. So, when the government introduces a new health initiative, it consults the public and usually secures citizens’ support.

Rumor has it

When it comes to vaccines against dengue fever or HPV which are not targeted at infants, there can be new layers of complexity to consider but trust remains a big factor. Where adolescents might be jointly making decisions about vaccines with their parents, social media can play an influential role.

Larson’s team has been monitoring media and social media for several years, scanning for signals of anti-vaccine sentiment or other indicators of waning trust in health authorities. This, combined with survey results, literature reviews and vaccine uptake rates, can help to give a holistic view of how the public feels about vaccines.

They have found that rumors spread through social networks – online and offline – and can cross borders. Not only can antivaccine stories spread to neighboring countries but myths also travel through linguistic and religious networks. False rumors about the polio vaccine have spread through Muslim networks while tetanus vaccine refusal traveled through Catholic networks from the Philippines to Africa and Latin America.

The ultimate goal is to build a system that can detect dips in vaccine confidence – or the outbreak of false rumors – before they take hold. Larson has been doing this for vaccines such as the pentavalent vaccine and for outbreaks of diseases including Ebola.

In a recent blog post, she noted how Facebook and Whatsapp were a conduit of anti-vaccine messages. By tracking these issues, it could become possible to target communication and engagement campaigns to where they are most needed.

“We are constantly putting out fires,” she says. “The idea of setting up a system to track vaccine confidence was to be able to gain resilience – to sustain trust rather than trying to fix it after it is broken.”