We speak to Mauricio Santillana, Boston Children’s Hospital and Harvard University, about his new paper on the use of Google searches in disease surveillance. Not only are search engines a vital tool for fighting dengue, they connect the community in a novel way, opening the door to crowd-sourced real-time outbreak monitoring.

What was already known, and what question(s) were you attempting to answer?

Multiple previous studies have explored the utility of using information from Internet searches to track disease activity in a given location. Google Flu Trends (GFT) is one of the earliest attempts aimed at tracking flu activity in the USA and other countries using flu-related Google search activity in the population. Unfortunately, GFT was shown to poorly track flu activity on multiple occasions and was discontinued in 2015. An array of studies has emerged, attempting to revisit the idea of using Internet searches to track diseases. In a recent study, our team introduced a methodology that leads to accurate tracking of flu in the USA at the national level using Internet search data.

Most of the previous research studying disease tracking with Internet search information has been conducted in developed and wealthy countries where internet penetration is high and healthcare-based disease surveillance systems have been in place for multiple decades. However, few studies have investigated the capabilities of using these novel methodologies to track neglected tropical diseases in less developed countries; similarly, the limitations of these methodologies, and how the tracking accuracy relates to the underlying characteristics of a country, such as Internet penetration and disease prevalence, are investigated by very few studies.

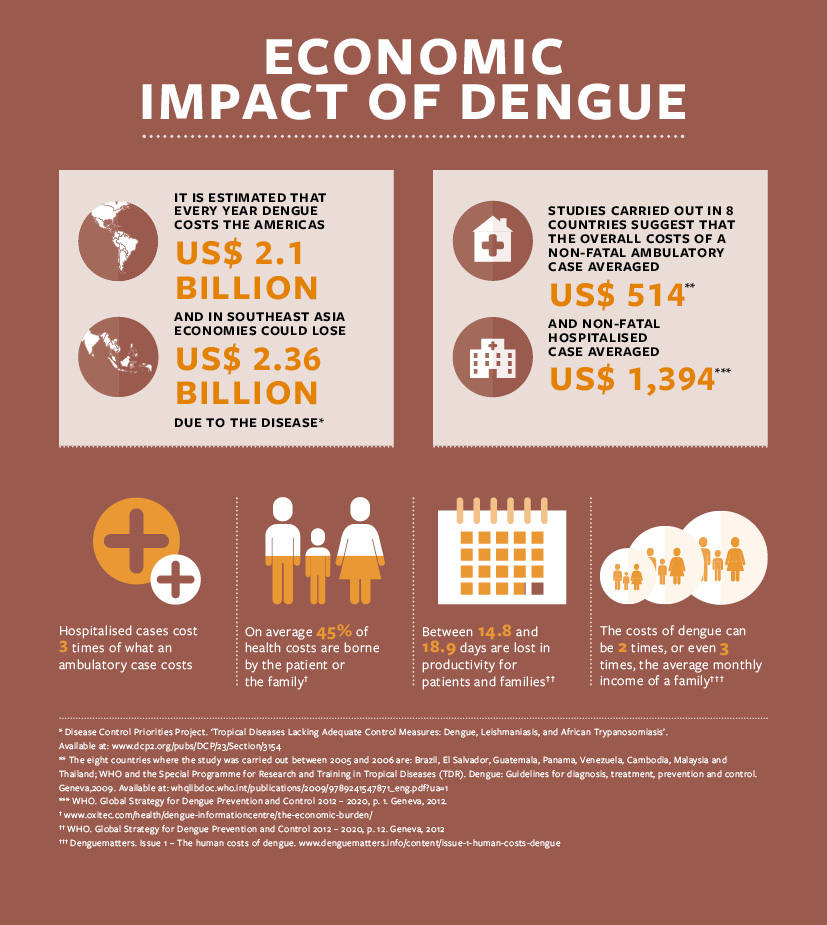

Read about the hidden economic cost of dengue

In this research, we studied the potential of using dengue-related Google search activity to track real-time dengue activity in five very distinct countries/states around the world: Mexico, Brazil, Thailand, Singapore, Taiwan. Specifically, we studied the capabilities and limitations of using Internet search activity to track dengue in less developed countries, as well as how the tracking accuracy relates to the underlying characteristics of a country.

What is the most important finding of your study?

By extending our methodology ARGO (AutoRegression with Google search queries), initially introduced for flu surveillance, to track dengue in these five countries/states, we show that:

(i) the lessons learned to track influenza in data-rich environments, like the United States, can be effectively used to develop methodologies to track an often-neglected tropical disease, dengue, in data-poor environments;

(ii) even in countries where traditional health care-based disease surveillance systems are lacking, properly developed methods using Internet searches of those countries can give accurate tracking of dengue;

(iii) our ARGO method significantly improves the tracking of dengue, which is particularly important for countries with less advanced clinical based disease surveillance systems, and

(iv) dengue-tracking methods based on Internet searches perform best in dengue-endemic areas with a high number of yearly cases and with sustained seasonal incidence.

What are the larger implications of your findings?

Previous inaccuracies of disease tracking systems such as Google Flu Trends and Google Dengue Trends led many public health officials to question the capabilities of big data approaches in tracking epidemic outbreaks. We show in our study that despite the discontinuation of Google Flu Trends and Google Dengue Trends, it is still meaningful to formulate, develop, and refine robust methodologies that are capable of extracting disease-related information from data sources not designed to do so.

In short, we have shown that information from Internet search engines can be used effectively to track mosquito-borne diseases with proper and rigorous statistical methods (i.e., analytics). This is particularly useful for less developed countries, where traditional clinical-based reporting systems are often delayed or missing. This alternative way of tracking disease can be used to alert governments and hospitals when elevated dengue incidence is anticipated, and provide safety information for travelers.

Based on your findings, what are the next steps for this research?

Future work should include investigating the feasibility of applying our methodology to other countries, finer spatial and temporal resolutions, as well as to other infectious diseases.

In a nutshell, what’s the most exciting aspect of the study?

The wide availability of Internet throughout the globe provides the potential for alternatives for reliably tracking dengue and other infectious diseases faster than traditional clinical-based systems. Such a development would be particularly useful for less developed countries, but proper and rigorous statistical methods are needed for the potential to be realized.

—

Click below to report dengue activity in your area.

However, only 27% knew a vaccine available and one-fifth of these said they would not have the vaccine due to concerns about a lack of data or safety issues. ‘Primary care physicians and other doctors need to educate themselves and be convinced that the vaccine works so that this sentiment can be conveyed to the patients and cascade down to the public,’ according to Dr. Ismail.

However, only 27% knew a vaccine available and one-fifth of these said they would not have the vaccine due to concerns about a lack of data or safety issues. ‘Primary care physicians and other doctors need to educate themselves and be convinced that the vaccine works so that this sentiment can be conveyed to the patients and cascade down to the public,’ according to Dr. Ismail.

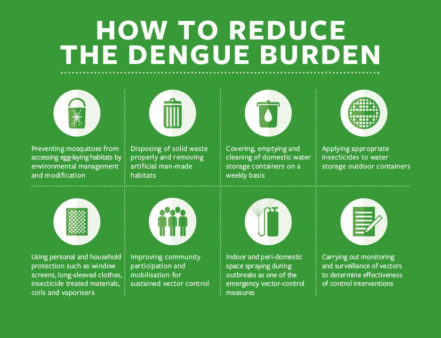

“Today, the great race to prevent and control dengue is a reality,” she says. “We encourage states and the scientific community to work together with civil society to prevent these diseases.”

“Today, the great race to prevent and control dengue is a reality,” she says. “We encourage states and the scientific community to work together with civil society to prevent these diseases.”