- by Alison

Dengue in Acre: how the virus took hold in a rural Brazilian state

Once the only state in Brazil to be free from dengue, investments aimed at developing rural Acre have, unfortunately, allowed Aedes aegypti to move in and thrive. Together, the movement of people, development projects, and unplanned urbanization have created the conditions for the dengue vector to spread and, establish breeding sites in the Amazonian region. Dengue in Acre has now reached epidemic proportions.

Turn the clock back 20 years to the mid-1990s. The Aedes aegypti mosquito is well-established across Brazil, having reinvaded the country since the 1970s. Dengue epidemics are commonplace across many Brazilian states and have been since the 1980s.

Increasing movement of people between growing Brazilian cities had helped the mosquito to spread. Immature and adult mosquitoes simply hitched a ride on lorries, trains, cars, buses and even planes. The virus hitched a ride too – on both infected mosquitoes and humans.

Meanwhile, fast-growing cities were providing the habitat for mosquito populations to grow. “An increased flow of people into Brazilian cities started in the 1970s,” says Raquel Martins Lana, Ph.D. in Epidemiology, Oswaldo Cruz Foundation. “The cities were not able to guarantee the infrastructure this influx needed, which led to poor infrastructure, low sanitation rates, water supply and garbage collection – and an increasing number of breeding sites for the mosquito.”

Acre, Brazil Photo courtesy of Raquel Martins Lana

Raquel M. Lana together with Marcelo F. C. Gomes (Oswaldo Cruz Foundation) were the primary researchers on a study exploring how “The introduction of dengue follows transportation infrastructure changes in the state of Acre, Brazil”. The project was led by Cláudia T. Codeço (Oswaldo Cruz Foundation), with the collaboration of Nildimar A. Honório (Oswaldo Cruz Foundation) and Tiago F. M. Lima (Federal University of Ouro Preto).

Acre: the final frontier

Development programs had yet to reach Acre. Lying relatively close to the Pacific Ocean and bordering Peru and Bolivia, this Amazon rainforest state was one of the last frontiers of development in Brazil.

Acre has great cultural diversity, with several indigenous peoples. In 1991 it boasted a population of just over 400,000 – a figure that has now almost doubled. Today, Acre has 18,240 indigenous people who inhabit 210 villages distributed across the state. Their indigenous lands make up 2,390,112 ha of 7,523,699 ha of protected natural areas – around 45% of the state.

“In the 1990s the state still had a relatively small population along with low urbanization and low industrialization up to the end of the last century,” says Raquel.

But Acre has seen significant investment and development since the turn of the century. Settlements and agriculture have emerged in previously unoccupied lands. “The population of some of Acre’s municipalities doubled between 2000 and 2010,” says Raquel. “And the percentage of people living in urban areas increased in 20 of Acre’s 22 municipalities during that time.”

In addition to allowing the change of land use, investment also allowed Acre to develop its major roads. The relatively recently completed Transoceanic Highway, for instance, channels Brazilian agricultural production via Ocean Pacific while the much-improved BR-364 highway links Acre to the neighboring state of Rondônia.

The arrival of dengue in Acre

It was during this period that the dengue virus was introduced into and spread across the state, almost 20 years after its introduction and establishment in Brazil.

While the first Aedes aegypti mosquito reached Acre in 1995, most probably arriving by road, Acre didn’t report its first cases of dengue until four years later, in 1999. “Acre’s first three cases of dengue are considered imported cases, which is also indicative of the importance of human travel to the introduction of the virus,” says Raquel.

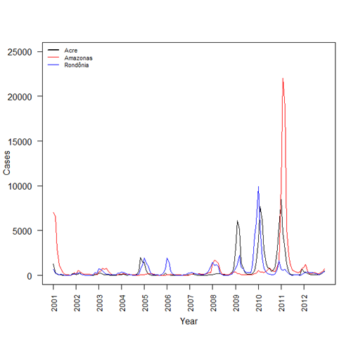

Acre reported its first autochthonous dengue case in Rio Branco, the state’s capital city and the main destination for travelers to the state, in 2000. Cases of dengue in Acre have grown rapidly since 2000. Today, incidence rates follow a similar pattern to the neighboring states of Amazonas and Rondônia and are consistent with endemic regions:

“The first dengue epidemic occurred in Rio Branco,” says Raquel. “Municipalities connected to the capital city registering epidemics sooner than more distant municipalities, many of which do not register autochthonous (local) dengue cases until the end of our study, in 2015.”

Dengue in Acre

Findings from the new study, published in PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases, suggest that the movement of people, development projects, and unplanned urbanization have combined to create the conditions needed for Aedes aegypti to establish itself in Acre. Raquel explains: “The mosquito had the means of transportation and favorable environmental conditions for introduction and fixation.

“The Aedes aegypti mosquito has a limited flight range, something between 50 to 200 meters. Therefore, it probably arrived in the state by road and then spread to the municipalities in a passive way, such as in cargo vehicles, passenger cars, aircraft, and containers.”

After all, Acre had improved its major roads, along with airborne access to the state; this had increased the number of trucks, containers and other vehicles moving around the state. Mosquitoes simply hop aboard as stowaways, taking advantage of the free ride from an infested area to an uninfected one.

Brazil port chief struck down by dengue in Paranaguá

Meanwhile, Acre’s many construction sites, unplanned urbanization (urbanization without improving the coverage of general services, such as garbage collection, water supply, and sanitary sewage) and population growth, not only provided ideal breeding sites for mosquitoes but also obstructed mosquito control.

Photo courtesy of Raquel Martins Lana

Despite the development programs, most of the municipalities in Acre are more rural than urban. These also have the conditions Aedes aegypti needs to establish itself once it reaches a village.

A stark warning

The study reconstructed how dengue most likely arrived and took hold into Acre, focusing on changes in infrastructure that improved access to cities, increasing the flow of people and urbanization. In essence, the study’s findings suggest that the development programs played a central role in the spread and establishment of the Aedes aegypti mosquito and dengue in Acre.

“Nevertheless, we should not stand in the way of development or view those projects as ultimately bad for the state,” says Raquel. “It is a strong warning against unplanned side-effects of such endeavors. These should be taken into account in the future to prevent them from happening.”

Photo courtesy of Raquel Martins Lana

“Our findings highlight the importance of establishing protocols within development projects that take into account the possible impacts on the ecosystem, so contractors take action to prevent the invasion of new vectors and their associated diseases.”

Do you have any stories about how you stopped dengue from invading your community? We’d love to hear what action you took.

—

Click below to create a record of dengue in your neighborhood.