- by Alison

Dengue in Cambodia: Using guppies and growth hormones to fight disease

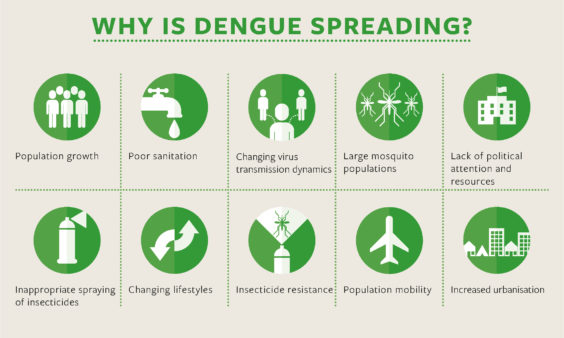

Image courtesy of the Malaria Consortium

Dengue in Cambodia is endemic all year round. But budgets are tight. For some time, The World Health Organization (WHO) and Asian Development Bank (ADB) have been helping the authorities search for a cost-effective and sustainable way to tackle dengue in Cambodia. A more recent research project (funded by UKAID and Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) with WHO as a partner) combined guppy fish, a larvicide based on disrupting growth hormones and COMBI (Communication for Behavioral Impact) activities.

Traditionally, Cambodian’s fight against dengue involves using chemicals to control the Aedes aegypti mosquito. But fogging hasn’t always had the desired impact. In 2015, for instance, there were 15,000 cases of dengue in Cambodia.

Over the years, researchers have tried other ways of reducing the Aedes population, with limited success:

- Initially releasing Mesocyclops (a crustacean that preys on mosquito larvae) into water containers where Aedes larvae live looked promising, but larvae numbers crept up over time. Also, people didn’t like crustaceans.

- Bacillus thuringiensis israelensis (Bti), a soil-dwelling bacterium, were found to significantly reduce larvae numbers in containers with river and well water, but only for two or three months.

- Jar covers with long-lasting insecticidal netting (LN) treated with deltamethrin eliminated two-thirds of adult Aedes, but they degraded over time, and children regularly used them as toys.

Hungry for larvae

One other approach, however, has had more success at decreasing the number of Aedes mosquitoes in Cambodia: guppy fish.

Between April 2006 and April 2007, a USAID-funded project tested the use of guppy fish in domestic water containers in 14 villages in the Kampong Speu province of Cambodia. Local volunteers bred and distributed the fish. On average, each guppy ate more than 100 mosquito larvae each day, significantly reducing the number of Aedes mosquitoes. After a year, only 10% of containers with guppies contained mosquitoes, compared with 50% of containers without fish.

Image via Malaria Consortium

“Guppies live quite well in Cambodia’s very hot and dry conditions,” says John Hustedt epidemiologist for the Malaria Consortium in Cambodia. “And they eat whatever larvae are in the water container.”

Following this success, the WHO and ADB funded a larger-scale IVM Guppy Fish Project, combining guppy fish with Communication for Behavioral Impact (COMBI) activities. COMBI uses communication and mobilization to improve the community’s behavior – rather than just attitude – towards water use and vector-borne disease prevention.

“They wanted to learn how to mobilize the community,” said John. “And to help the community understand how and why they’re using guppies.”

Tackling smaller breeding sites

The project, however, had its limitations: other Aedes breeding sites, including containers too small for guppies to survive in, still needed to be tackled.

A product based on Pyriproxyfen (PPF), a growth hormone that prevents juvenile Aedes mosquitoes from developing into adults, looked promising. When studied in Cambodia in 2003, it stopped 90% of Aedes larvae maturing for 20 weeks. During the study, researchers placed a controlled-release formulation of pyriproxyfen consisting of cylindrical resin strands in concrete water storage jars between 400 and 500 liters in size.

However, maker Sumitomo Chemical never released this specific solution for technical reasons. The company has since reformulated the PPF-based solution, developing and releasing the slow-release formulation called SumiLarv® 2 MR.

The local community can use this controlled-release disk in water jars too small for guppy fish while cutting the cost of larviciding since it only needs to be distributed once every six months – the whole rainy season. John explains: “Normally, you’d put larvacide pellets into water containers up to six times a year. This controlled-release disk can, therefore, save on operational costs.”

Added to that, SumiLarv® 2 MR can work at very low levels. “It doesn’t kill the mosquitoes; it’s just a growth inhibitor that messes with the mosquitoes’ hormones,” says John.

A combined approach

John and his team initiated a trial to study how effective combining guppies, PPF and COMBI activities would be. The study site included approximately 6,000 households, divided into three groups:

1. Guppies, PPF and COMBI activities

2. Guppies and COMBI activities

3. Standard vector control activities from the Ministry of Health

Groups one and two placed two guppy fish into water containers bigger than 50 liters; their COMBI activities included health education sessions, posters, banners, t-shirts, and songs. Group one also placed one SumiLarv® 2 MR disk in containers of between 10 and 50 liters.

Image via Malaria Consortium

Guppies accepted well

Local people tended to like using the guppies, even if they hadn’t used them before. Not only are fish were seen as lucky, but the people of Cambodia traditionally use fish for health interventions.

Even though previous studies have shown guppies don’t significantly increase e.coli or other bacteria in water jars, a few people – mainly foreigners – still questioned the practice. “We talked to them about how there were fish in the lake where they get their water,” says John. “It was then no longer an issue.”

John is also very conscious that some outsiders are concerned that the guppies could upset the balance of the local ecosystem. “While introducing a non-native fish species into the ecosystem could hurt the local fish and deplete oxygen levels, guppies have been here in Cambodia for many years,” says John. “I haven’t seen any peer-reviewed scientific evidence of harm in Cambodia.”

“I think it’s a valid concern, which we should think about; but without evidence to the contrary, I don’t think it’s a reason why we shouldn’t use guppies,” John continues. “You could potentially distribute only fish from one sex, so they don’t breed if they do get into the water.”

Religious concerns

Local people, however, were more concerned about using the PPF devices. “We created COMBI messages that local volunteers could use to explain that PPF is at a very low level that doesn’t kill the larvae and isn’t harmful to people,” says John. “After a while, their reservations were gone.”

People’s main concern, however, was grounded in their religion. Older people with strong religious beliefs didn’t want to use guppies or PPF to kill the larvae because they were living creatures and it would be frowned upon. “We explained that, while it’s important for us to treat living creatures nicely, if you don’t get rid of the mosquitoes then dengue transmission will continue and some children will die – even children in your community,” says John. “We told them, ‘You have to choose between getting rid of the larvae or people becoming sick and possibly dying’.”

Image courtesy of Malaria Consortium

The researchers also explained that they didn’t want people to kill the larvae, just to introduce this fish. “We told them that the fish are part of the normal eco-system and this is how the fish need to survive,” says John. “It’s part of the normal circle of life.”

So far, so good

Throughout the study, which ran from October 2015 to September 2016, the number of adult Aedes females per household was significantly higher in the group using traditional methods. The study, which won the 2017 Break Dengue Community Action Prize, also found that people accepted guppies well and liked the SumiLarv® 2 MR devices, though the community needed to understand how PPF works and the role of the adult mosquito in the transmission of dengue in Cambodia. Furthermore, a tailored engagement approach and communication materials using COMBI led to high levels of community acceptance and participation.

On the question of sustainability, while it is probably too early to say if it will be sustainable in the long run, the guppy fish are still there. “We were able to follow-up thanks to prize money from Break Dengue. We met with the guppy bank and the health center folks using the guppy bank. People are still enthusiastic about it, but we need to see how it progresses with time,” concludes John.

How is your community taking the fight to dengue? We want to hear your stories.

—

Click below to report dengue activity near you and get access to up-to-the-minute, crowdsourced reports on outbreaks.