- by Alison

Sri Lanka dengue outbreak: IFRC are joining forces to fight back

Image via IFRC

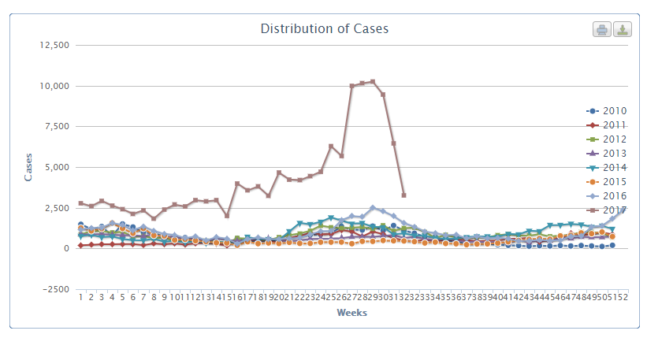

Flooding last year and the arrival of a new serotype: the lethal combination behind this year’s dengue outbreak in Sri Lanka – the worst outbreak the country has ever seen. This Sri Lanka dengue outbreak has affected 15 out of Sri Lanka’s 25 districts, which are home to almost 600,000 people. By mid-August, the Sri Lanka Ministry of Health (MoH) had reported more than 134,000 new cases of dengue, including 38,835 new cases in July alone – a nearly fourfold increase on the previously recorded 10,715 cases seen during July 2016. Numbers are now decreasing, thanks to the combined efforts of the MoH, the Sri Lanka Red Cross, the International Federation of the Red Cross (IFRC) and the World Health Organization (WHO).

Deadly floods provide a home for Aedes

Dengue has been endemic in Sri Lanka for more than 30 years, maintained by the country’s annual monsoon rains. In fact, the severe flooding seen last year is likely to be a key factor in this year’s Sri Lanka dengue outbreak.

Why? According to dengue experts in Sri Lanka, the Aedes aegypti mosquito lays eggs in stagnant water, in this case, the stagnant flood waters from the heavy monsoon rains. Even why the flood plains dry out, these eggs can survive up to one year. They then grow into larvae as and when they come in contact with water; in other words, during the following year’s monsoon rains.

Gerhard Tauscher, Operations Manager with the IFRC stationed in Columbia, explains how this life cycle has played out in Sri Lanka: “Some of the districts of Sri Lanka that tend to see dengue were affected by flooding in May last year. The larva status mosquitos we see now are probably from eggs laid last year, triggered by this year’s monsoon rain, which started on the 25th of May. This pattern plays out every year.”

While the number of dengue cases was already high at the start of the year, by May, case numbers were spiraling out of control. “Almost 16,000 cases were reported in May,” adds Gerhard.

The arrival of a new serotype

So why what this year’s Sri Lanka dengue outbreak so much worse than other years?

One explanation is the arrival of a new serotype, as reported in a recent WHO news article:

“Dengue fever is endemic in Sri Lanka and occurs every year, usually soon after rainfall is optimal for mosquito breeding. However, DENV-2 has been identified only in low numbers since 2009 and is reportedly over 50% of current specimens which have been serotyped.”

Basically, the local population has built up long-term immunity to the serotypes normally seen in Sri Lanka. However, people’s resistance to DENV-2 is very low, meaning more people are getting sick when they’re infected. This, in turn, increases the Aedes aegypti mosquito’s ability to spread the disease – reflecting the high number of DENV-2 cases.

Furthermore, this recent Sri Lanka dengue outbreak started in the North and the East, which is where the new serotype is most likely to have reached the country.

Hospitals overwhelmed

Hospitals quickly became overwhelmed quickly; some of them had to convert other wards, including maternity wards, to dengue wards to accommodate the higher number. The WHO helped increase the number of beds available, creating three temporary wards in a hospital in the province of Gampaha, 38km north of Colombo. This was the first hospital to approach the Red Cross.

“The local branch of the Sri Lanka Red Cross immediately began to make their volunteers available to help the hospital cater for the large numbers of people arriving,” says Gerhard. “First aiders went there to help by providing social services: mainly moving patients, and bringing food and water.”

In addition, the IFRC team based in Sri Lanka launched its emergency response program towards the end of July after receiving 295,000 Swiss Francs of international funding from the IFRC Disaster Relief Emergency Fund earlier in the month.

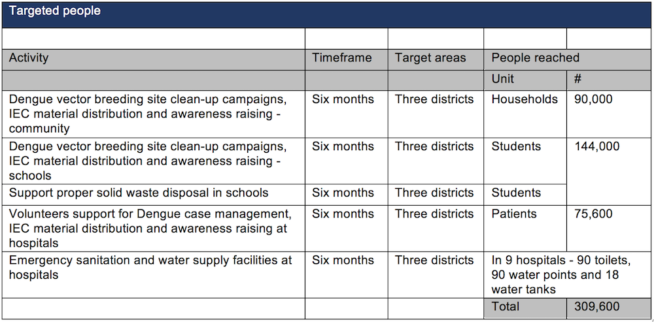

The vital funds will support a six-month program that builds on current clean-up campaigns, raising awareness and providing emergency sanitation for stretched hospitals who asked the IFRC to provide additional water storage and toilets because of the high numbers of patients.

IFRC volunteers in Sri Lanka Red Cross Society campaigning to prevent outbreaks of dengue.

Part of the bigger machinery

The IFRC response builds on the MoH’s own emergency response. The army, police and civil defense forces are conducting house-to-house visits in high-risk areas, supported by health staff and teams of Sri Lanka Red Cross Society volunteers. These visits aim to raise awareness about dengue and mobilize the community: how to treat symptoms, prevent mosquito bites and get rid of waste and stagnant water. The Red Cross volunteers are also helping authorities identify and clean mosquito breeding grounds.

Read: Dengue home remedies. Do they really work?

IFRC volunteers carry out dengue inspections in Sri Lanka. Image courtesy of the IFRC

In fact, Sri Lanka has a relatively well-established public health inspector system with one person supporting around 3,000 families. While the inspectors, who know their neighborhood well, monitor all aspects of public health; their current focus is on dengue.

Efforts are paying off. The number of dengue cases reported fell significantly in August.

Sri Lanka dengue outbreak: long-term focus

The IFRC is now preparing to launch a longer-term program, once the country is no longer on high alert. This program will focus on dengue prevention during the dry period when Aedes aegypti eggs lie dormant in dried out flood plains.

Gerhard explains why: “Traditionally, people are not very proactive. Things are easily forgotten. If the number of new dengue cases drops for just a couple of weeks, dengue will no longer be in the headlines or media – and it will be out of everybody’s head.”

IFRC is launching an emergency appeal to raise funds for Sri Lanka, so the country will have for at least one year of funding to help on two fronts: firstly, to disrupt dengue lifecycle and, secondly, to ensure its preparation for the next Sri Lanka dengue outbreak. “We want to support the existing system so a public health inspector can get the extra hands he needs to go to all the houses where there is suspicion and bring that under control,” says Gerhard.

Dengue surveillance will also play a key role in this program. It will put a system in place where teams always follow up on anyone admitted to hospital with dengue, tracing back to their home and workplace to try to identify where the infected mosquitos came from. “That will be more of a mandate to really get on top of eliminating dengue,” adds Gerhard.

In addition to that, the Eliminate Dengue Program (EDP) has established a research partnership with the MoH to pilot Wolbachia bacteria infected mosquitos in Sri Lanka.

Impact on the local economy

With tourism a critical part of its economy, Sri Lanka is keen to ensure visitors are not deterred. After all, dengue is all around the equator in 100 countries. Whether there’s an outbreak or not, tourists are always a high-risk group in any of these tropical countries, simply because they haven’t built up any immunity to the disease.

“The situation for tourists has not changed dramatically,” says Gerhard. “As a tourist, you most likely don’t have any resistance against any of the dengue serotypes. You must use nets and repellent as standard when traveling to mitigate the risk of catching dengue.”

While the recent Sri Lanka dengue outbreak is the result of heavy rains, flooding and the arrival of the DENV-2 serotype, the key to breaking the annual dengue cycle in this dengue-endemic country likes in keeping dengue prevention high on the agenda all year round.

—